サブ・スタンダード船と旗国の関係

SUBSTANDARD SHIPS AND FLAGS

SUBSTANDARD SHIPS AND FLAGS

UNDER-PERFORMING SHIPS (1年間に3回以上出港停止を受けた船舶) TOKYO MOUのHP

船に関してあまり知らない人は、旗国と聞いても何が旗国と疑問に思うだろう。

旗国とは船舶が登録されている国を意味する。船の船尾に船舶が登録されている国の国旗が掲げられている。ここから旗国と呼ばれるのである。

船舶登録や管理を外部に委託している制度を採用している国もあるが、基本的には登録されている船舶に関しては旗国の責任である。(*)

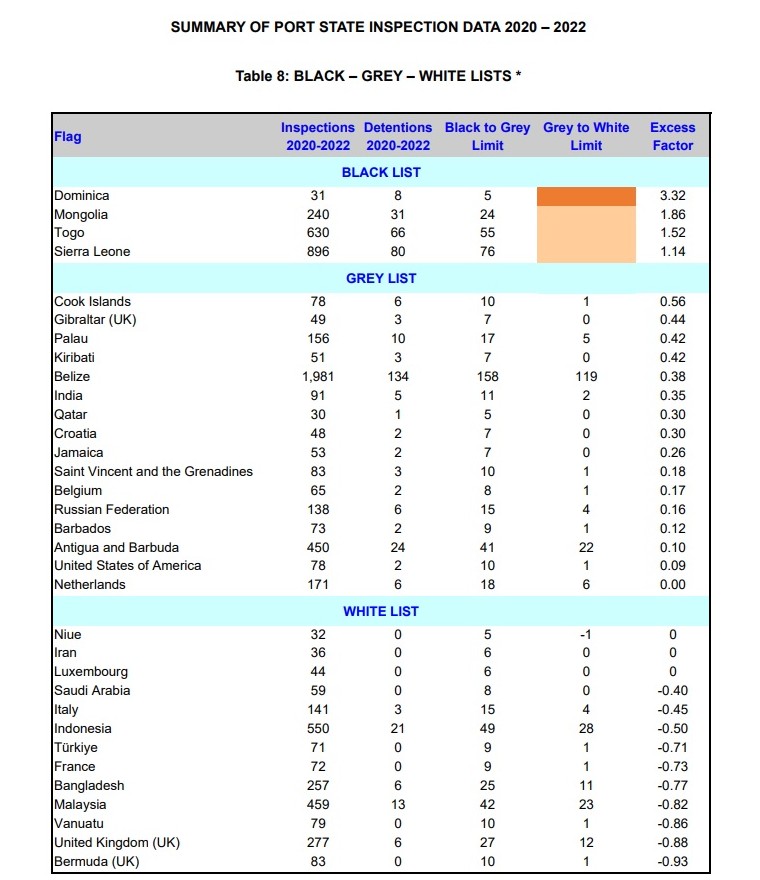

上記の10年後のデータを比較すると10年経っても大きな変化がない旗国が存在する事がわかる。つまり、変わらない、又は、変われない旗国が存在する。そして

PSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール)による検査が世界中で行われているが、 カンボジア籍船が制裁措置の影響で消えた以外、大きな変化は起きていないと考えれる。

カンボジア籍船が制裁措置の影響で消えた以外、大きな変化は起きていないと考えれる。

「便宜置籍国」は税金対策よりも規則が緩い国籍に登録する事によりいろいろなコストを抑える事が出来るメリットがあると思う。

例えば、規則があっても規則を守らせようとするコントロールが甘いのもメリット。規則を守らなくても問題ない。問題を指摘されるまで

は問題を是正する必要はない。このような問題があるので、PSCによる検査が

強化され、世界中で寄港国の政府職員による検査が頻繁に行われるようになった。

PSCによる検査(寄港国の政府職員による検査)が甘ければ、

サブスタンダード船であっても入港できるし、出港停止命令も受けない。

船の運航及び維持管理費が安くなれば利益がアップするのは間違いない。例えば、規則を満足するのに1億円ほど必要であるが、

船の国籍を特定の国籍にすれば、2千万ほどに出来る場合がある。この場合、差額が利益アップに貢献する。違法なので問題が

発覚すれば終わりであるが、なかなか指摘を受けない場合もあるし、約10年ほど運航しても指摘を受けない場合もある。

このようなケースがあるから、特定の国籍にサブスタンダード船が登録される傾向が高いのである。

中東レバノンに逃亡した前日産自動車会長カルロス・ゴーン被告のケースを考えれば理解しやすいと思う。船の国籍を変える事、そして、国のシステムに問題がある事が上手く重なり合えば、違法な行為でも簡単に処分されない。

PSCはこの事実を理解して対応しないと、自国の領海や沿岸で便宜置籍船が海難や座礁の結果

放置船になり、税金で撤去されるはめになる。

フィリピンでの船舶による油流出事故ではISOの認定を受けていた検査会社の不正やフィリピン沿岸警備隊職員の汚職疑惑が表に出た。船齢が1年の船が実は船齢50年以上で建造された日から6か月間に4回もフィリピン沿岸警備隊職員よる検査を受けたにも関わらず、船が沈没して大規模な油汚染が発生するまで、問題ははっかくしなかった。システムが存在してもシステムが機能しなければ、不正は可能であることが部分的に証明されたケースだと思う。

フィリピンでの船舶による油流出事故ではISOの認定を受けていた検査会社の不正やフィリピン沿岸警備隊職員の汚職疑惑が表に出た。船齢が1年の船が実は船齢50年以上で建造された日から6か月間に4回もフィリピン沿岸警備隊職員よる検査を受けたにも関わらず、船が沈没して大規模な油汚染が発生するまで、問題ははっかくしなかった。システムが存在してもシステムが機能しなければ、不正は可能であることが部分的に証明されたケースだと思う。

By Paul Peachey in London

Tanzania, Togo and Belize have been identified among the world’s worst performing flag states by three separate port inspection regimes.

Tanzania secured the unwanted tag of being labelled “very high risk” on the blacklists of the Paris and Tokyo port inspection authorities and as “high risk” by the US Coast Guard.

The three flag states feature in a short joint submission filed by the port state control regimes to the International Maritime Organization as the regulator looks at ways of harmonising inspection programmes around the world.

by Joshua Minchin

Tanzania was the only flag state featured in the highest-risk category for Paris MOU, Tokyo MOU and US Coast Guard

BY ALLAN E. JORDAN

Shipping is in transition with emerging regulations, the drive for decarbonization and geopolitical issues all increasing the pressure on both ship registries and classification societies. The pandemic impacted the business by driving up cargo volumes and demand for containerships. More recently, the war in Ukraine and implementation of sanctions impacted dry bulk, tanker and gas carrier usage.

All of this comes as shipowners and operators had to deal with increasing financial pressures and a growing shortage of qualified merchant sailors.

Responding to these issues, ship registries (flag states) are rethinking their role and how they work with owners. While finding themselves challenged as more shadowy operators seek to skirt regulations, flags – like class societies – are becoming more like advisors to the industry. They’ve also had to incorporate new technologies to address trends such as digitalization as they change the way they do business.

Sanctions & Flag-Hopping

Increased sanctions over the past two years have placed a growing burden on registries. Flags and class societies alike have responded by increasing the number of ships and operators they’ve suspended and removed from their ranks. All the flags are also reporting that they’ve increased their vetting efforts to stop “flag hopping” and other deceitful practices.

Coming under pressure to address sanction busters, the Panama Maritime Authority – which for many years has been the largest registry – says it’s canceled more than 6.5 million gross tons since 2021 for issues related to Iran and North Korea or vessels included on the lists of international sanctions.

In an effort to stop operators or ships from hopping between flags, Panama together with two of the other leading international flags, the Liberian Registry (LISCR) and the Marshall Islands Registry (RMI), has had an agreement since 2019 for the exchange of information. It helps them identify ships being removed from a registry and seeking replacement flags.

The vetting of ships and their operators has also taken on new importance. The Liberian Registry, for example, which has grown rapidly to rival Panama, has taken significant steps to enhance its capabilities by collaborating with outsourced services to strengthen its ability to access accurate and up-to-date information. The Cayman Registry, a leader in yachting, is only accepting registrations from individuals or companies located in jurisdictions with stringent fiscal and anti-money laundering regulations.

Rise in Detentions

Financial challenges created by shifting markets and supply chains are further increasing the pressure on ship operators. Flags believe this has led to the increase in abandonments and lax compliance by some marginal operators with the Maritime Labor Convention, maintenance and safety regulations. The Paris MoU, one of the largest port state control authorities, reports that detentions were at their highest rate in 10 years in 2022.

Ship quality issues and the rise in detentions have also seen flags slip from the top-level White List to the more audited Grey List.

Authorities like the Australian Maritime Safety Authority have increased their enforcement efforts. AMSA, for example, reports that so far in 2023 it’s issued bans on five ships and has 18 operators under monitoring programs due to a history of deficiencies. Even a private organization, the International Transport Workers Federation (ITF), announced in March an eight-week surge in inspections seeking to root out safety, maintenance and seafarer welfare failings.

The Korean Registry (KR) believes the number of inspections has returned to pre-pandemic levels, contributing to the global increase in detentions. The Liberian Registry highlights “the lack of standardization among Port State Control inspections and the detainable items and what can be rectified before departure.”

Additional factors include the overall growth in the size of the global fleet as well as the increasing average age of vessels. Because of the size of its registry, Panama’s more than 8,500 ships receive more than 14,000 inspections annually. Panama concedes that, while it’s been effective at attracting over 1,500 new ships to the registry in the past four years, the age of its legacy fleet contributes to detentions. More than a third of the ships registered in Panama detained in the Paris MoU in 2022 were more than 30 years old with 35 of them more than 40 years old.

“Tidying up” has become a key issue for the Panama Maritime Authority. Since 2021, it’s begun efforts to actively purge the registry of the oldest ships and ones that do not follow best practices. Panama has also introduced pre-inspections and other steps for vessels calling in the U.S. to ensure compliance, especially for ships that might – because of their past history – be targets for USCG Port State Control inspections.

These steps were introduced as the PMA for the first time entered the U.S. Coast Guard’s Qualship 21 program, a milestone for the flag administration.

Other flags, including the Marshall Islands, say they’ve also increased their vetting considering issues like age with RMI highlighting its pre-registration inspections and 19 consecutive years of participation in the Qualship 21 program.

Many have introduced new tools to help owners prepare with the Korean Register offering a new app that provides real-time information designed to reduce the risk of PSC detentions. Liberia has a Dynamic Prevention Program that, among other capabilities, automatically generates notices with a risk assessment when destinations are entered into a ship’s AIS system.

These efforts are not exclusive to the largest flags. Cayman provides support before, during and after PSC inspections and has a Fleet Quality Management system.

Environmental Issues

The Liberian International Ship & Corporate Registry (LISCR), which administers its flag, calls decarbonization and growing environmental regulations “probably the most contentious issues” for the shipping industry.

The IMO’s Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) have each gone into effect and are expected to have significant financial consequences for operators. The IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee also recently adopted a dramatic acceleration in the industry’s decarbonization timeline.

“There’s a lot going on behind the scenes on the environmental/emissions fronts,” notes LISCR. Flags and class societies are actively working with organizations including shipbuilders to develop new vessel technologies. Liberia, for example, is in partnership with Lloyd’s Register on a project to develop a large multi-gas carrier while KR is working on projects including a liquefied CO2 carrier and methanol-fueled tanker designs.

“Palau International Ship Registry is making significant strides in promoting green shipping practices,” says the registry. It points to programs such as a Blue Certificate to recognize clients who comply with environmental regulatory regimes and also donates $5 to the Palau Marine Sanctuary for every invoice issued, demonstrating a commitment to the marine environment. Panama highlights its efforts in promoting the construction of eco-friendly ships.

The time has come, says the Marshall Islands, for owners and operators to determine their path forward to decarbonization. As owners access and implement their approach, flags are working to provide increasing levels of technical support and guidance. The Marshall Islands has launched a Gas and Renewables team to help reduce the risk of regulatory “surprises.” Cayman says it understands the difficulties its clients are encountering as a result of the uncertainties surrounding alternative fuels and has launched new efforts to assist.

The IMO’s regulations are not without controversy, and flags are taking an active role in representing clients’ concerns to the IMO. Palau, for example, supports the IMO’s CII and EEXI initiatives but “believes that the IMO should address industry concerns and collaborate with stakeholders to develop a more comprehensive and adaptable system.” The Cayman Registry is helping clients “ensure that any unintended consequences of GHG emissions from EEXI implementation are addressed at the IMO before 2026.”

“Owners need qualified and experienced partners as they navigate the decarbonization challenge as well as an intimate understanding of the direction of the regulatory discussions,” says the Marshall Islands Registry.

New Technology

In the wake of COVID and emerging environmental regulations, efforts are growing to adopt new ways of operating and, for example, reduce dependence on physical documents. Panama, for example, is overhauling its model and working with legislators to modernize and streamline administration of the flag.

A big part of the effort is the adoption of new technology. Panama’s upgraded systems provide new automatic notifications, minimize the requirement and handling of physical documents and allow users to make inquiries. Similarly, Liberia has a popular Duty Officer Video Call feature that permits shipowners to get live video support and share documents in real time.

“The biggest challenge facing all classification societies is how to best harness the power of digitalization,” says KR, noting its use in driving decarbonization. It adds that 22 percent of its Busan headquarters workforce is dedicated to R&D dealing with new technologies. KR is developing remote survey technologies and plans to launch an integrated digital service platform in 2023 as well as a data exchange system.

One of the biggest challenges involves technology getting ahead of regulations. An example is autonomous navigation where KR is working with HD Hyundai and its subsidiary Avikus on autonomous navigation technologies and how to integrate them into future operations. Marshall Islands has also invested in building strong technical teams with experience in emerging new solutions.

Leading the Way

Owners need qualified and experienced partners as they navigate the growing challenges and coming transitions in ship operations. Ship registries are working to fill this role along with class societies. Understanding and anticipating the regulatory direction will be critical going forward, and that’s where the registries can lead the way.

Allan Jordan is Associate Editor of The Maritime Executive.

By: The Maritime Executive

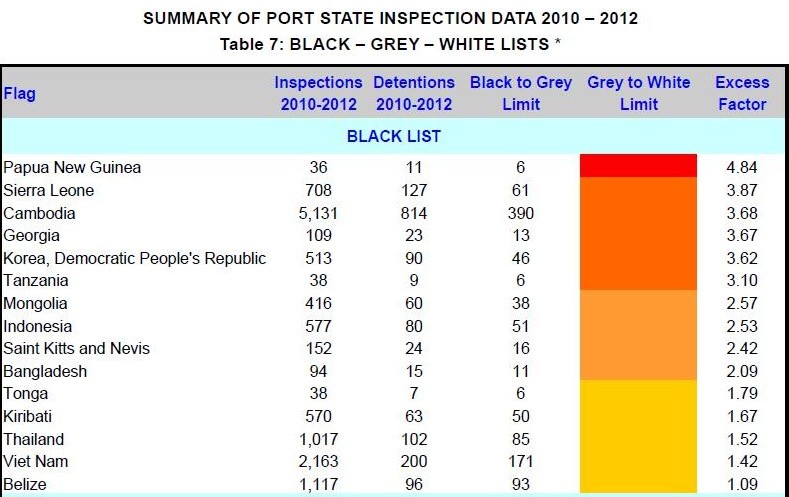

Panama has released new details of its program to clean up its fleet, including efforts to bring up the quality standards of its recognized organizations and inspectors.

Prompted by the downgrading of its flag to the "gray list" of the Paris MOU, Panama has embarked on a mission to improve its port state control performance, and it has described the effort as a "paramount issue." The changes include tightening scrutiny of new applicants to the flag, attracting more newly-built ships, rejecting ships over 30 years of age, evaluating the quality of older legacy tonnage, and high-grading the fleet, as announced last week. Panama is also taking the step of cracking down on sanctions-busting and illegal fishing.

But in a new statement released Wednesday, the Panama Maritime Authority added that it is going a step beyond the examination of its clients and their tonnage. It is also looking closely at the quality of oversight provided by its recognized organizations and inspectors.

According to the flag administration, it has picked up a trend of high levels of deficiencies and detentions for ships with valid documents from certain ROs. Panama has audited these ROs, and some have been suspended. Revocation of their status is a possibility going forward.

Panama has also picked up on issues with flag state inspections carried out by some of its approved inspectors. In some of these cases, the inspector never attended the ship and carried out the task remotely, without approval from the flag state. So far, Panama has suspended three inspectors for poor performance, and 14 more are in the process of suspension. An additional nine have been canceled from the approved inspection list altogether.

下記の記事はPanama Maritime Documentation Services (PMDS)と呼ばれるパナマから承認されている検査会社と検査官達の不正である。また、International Maritime Survey Association (IMSA)と呼ばれるモンゴルから承認されている検査会社と検査官の不正に関して書かれている。記事は北朝鮮、又は、北朝鮮に関与している船に関して証書を発給している事だけに言及している。

PSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員や国土交通省がどこまで情報を持っているのか知らないが、これらの検査会社は北朝鮮、又は、北朝鮮に関与している船に関して証書を発給している問題だけでなく、国際条約を満足していないサブスタンダード船に対して、船が運航できる証書を発給している問題がある。最近、ビックモーターの問題が注目を浴びているが、もし、国交省がPanama Maritime Documentation Services (PMDS)が検査したサブスタンダード船に対する検査程度の調査しかしなければ、甘い対応で終わりであろう。残念だが、個人的にはPSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員の検査は甘いと思う。また、検査する船や検査する項目が的外れだと思う。本当の意味での取り締まりであれば、問題があると思われる船に絞るべきだと思う。良い船を検査して、検査官の数が足りないから全ての船を検査できないとか言っているのであれば、本当にあんぽんたんか、やる気がないと思う。

PSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員の検査が甘いと、たくさんのサブスタンダード船が日本に入港するので、入港及び出港の過程で事故を起こす可能性はある。そして、放置される可能性はある。放置されると日本国民の税金で撤去される事となる。

地中海で運航されているクック諸島船籍、 ![]() パラオ籍船、

パラオ籍船、 シエラレオネ籍船、

シエラレオネ籍船、![]() トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われる対しての抗議の記事だけど個人的には問題のある旗国は実際に問題が多い。

トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われる対しての抗議の記事だけど個人的には問題のある旗国は実際に問題が多い。

旗国と旗国に登録されている船の検査を行う検査会社には資本提携関係はない。よって、問題のある検査会社を承認する、又は、代行して検査させる事を了承して、問題が発覚するまで放置する事は可能。問題責任を追及されれば、問題を知らなかった、又は、報告されていなかったとコメントして、逃げ切れなければ問題のある検査会社の承認を無効にすることで逃げる事は可能だと思う。フィリピンで沈没した油汚染被害を起こした小型タンカーがこのケースに当てはまるのかは全く分からないが、少なくとも普通の常識では起きない事が起きている。タンカーを検査した検査会社はフィリピン海運局から代行して検査を行う権限を無効にされた。

旗国の責任として逃げれない部分があるとすれば、旗国による年次検査であろう。多くの旗国はコスト削減のために外部の検査会社やフリーランスの検査官と契約しているケースが多い。問題のある(グレー、又は、ブラック)旗国はまともな検査官を集める事は個人的には不可能だと思っている。まともな検査官が検査すれば、問題のある検査会社が故意に見逃した、又は、お金儲けのためにろくに検査せずに検査に合格した証として証書を発給しても、問題を見つけるだろう。そうなれば、インチキが出来る、又は、問題があっても船を運航できる理由で特定の旗国を選んだ船主は他の旗国へ移るだろう。問題のある(グレー、又は、ブラック)旗国に登録される多くの船はサブスタンダード船なので収入源が消失してしまう。だから大ナタは振えない。サブスタンダード船であっても不備を見つけられるとは限らない。個人的にはPSCの検査は特定の国や港を除けば厳しくないと思う。問題を見逃してもPSCの検査はランダムチェックなので全てを見ていないと言い訳が出来るシステムの存在もある。結局、上から厳しい検査をするように命令がなければ適当に検査をしているのが楽だと推測する。これが大きく現状が良くならない理由だと個人的に思う。International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) は船員に関係しない部分に対しては興味を示さない傾向があると個人的に思う。だから問題のある検査会社に関して興味がないように思える、又は、問題解決に興味を示さないように思える。まあ、検査官の多くは元船員なので矛盾があると言えば、矛盾があると個人的に思う。結局、関係がない船員(安全や命)の事よりはお金儲けが優先だし、問題のある(グレー、又は、ブラック)旗国に関わる人間はその傾向が高いと個人的には思う。これは船員に限った事ではなく、人間の傾向だと思う。知らない人の事は興味を示さない傾向が高いし、他人事であれば、人は冷たくなれるし、実際的にはそれが普通だと思う。だからこのような問題は大きな進展は期待できない可能性が高いと思う。

By Paul Peachey in London

The number of ships detained under the Paris MoU hit the highest level for a decade in 2022, with port authorities forced to take on a greater role in tackling substandard vessels.

The organisation’s annual report revealed that more than 4% of vessels were detained from 17,289 inspections and took a sideswipe at flag states, and the recognised organisations that carry out inspections on their behalf, for not playing their part.

Some of the most frequently recorded deficiencies in 2022 included problems with fire doors, seafarer contract issues and the cleanliness of engine rooms, the

report said.

“While a direct link to Covid-19 cannot be easily established, it is concerning that the 2022 detention rate is the highest in 10 years,” the report said.

“This has increased the importance of port state control as a line of defence, where others — in particular shipowners, flag states and recognised organisations — fail to take their responsibility sufficiently.”

The report said detentions have declined slowly but steadily for years before the 2022 figures. The detentions represent 723 vessels but include some that were held more than once in the year.

“We hope, and in fact assume, that the chain partners in the maritime sector ... will also take measures to put a stop to this negative trend,” Paris MoU chairman Brian Hogan and secretary general Luc Smulders said.

The highest proportion of detentions was for ships flagged by Moldova, according to the figures, with 10 detentions of 32 vessels inspected — or 31%.

Cameroon was second on the list with 27% of vessels inspected. Vessels flagged by Tanzania, St Kitts & Nevis and Algeria all had detentions of ships above 15% of those inspected, according to the report.

The Paris MoU also reported a slight downward shift in quality of shipping as measured by its white, grey and black lists of flags. The list status is calculated based on three years of rolling data with at least 30 inspections

during the period.

Dark fleet

White-list flags was down one from 2021 to 39, while nine flag states were black-listed in 2022, up from seven in 2021. The nine are Cameroon, Moldova, Algeria, Togo, Albania, Vanuatu, Sierra Leone, Comoros and Tanzania.

A number of those have been prominent in flagging the so-called “dark fleet” tankers, hauling sanctioned oil cargoes from Iran, Venezuela and Russia. They include Cameroon, Togo and Sierra Leone.

St Kitts & Nevis, which is on the grey list but was in the top five flags for detentions in 2022, dropped a number of vessels managed by India’s Gatik Ship Management earlier this year amid suspicions of sanctions-busting linked to Russian oil shipments.

The inspections in 2022 marked a return to normal operations after two years of lower activity, owing to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Paris MoU agreement includes 26 European coastal states and Canada. Russia is currently suspended from the organisation because of its invasion of Ukraine.

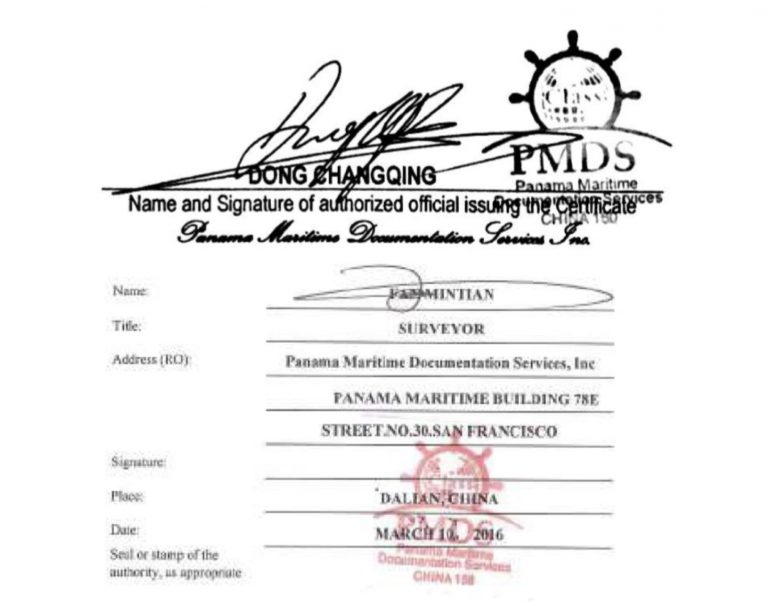

By Gary Dixon

The flag states of Togo, Palau and Sierra Leone have expressed anger and frustration at being targeted for a crackdown on shipping standards in the

Mediterranean.

The trio was listed by the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) as among the four worst in the region, together with the Cook Islands, and will be the subject of an inspection campaign involving up to 1,000 ships.

Sierra Leone objected to being described as on the Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control (Paris MOU) black list of underperforming flags, when it has been upgraded to the grey list.

Togo believes its efforts and achievement on safety and sanctions compliance were overlooked.

And Palau is suggesting a meeting with the ITF to advance seafarer safety.

Registrar Vera Medawar, of the International Ship Registry of Togo (ISRT), told TradeWinds the organisation is disappointed with the union’s statement, due to Togo’s “sincere efforts and cooperation with them to solve all the issues that we have faced in the past”.

“Really, we don’t know why ITF is targeting any flag administration, since it is obvious that when a vessel is abandoned by the owners it’s for financial or economic reasons that the flag administration has no relation with,” she added.

The ISRT said the Togo Maritime Administration has undertaken “severe” measures to upgrade performance.

These will need some time to show a significant improvement, “but we have set the path and we are implementing the measures accordingly”, it added.

Since January, 44 new ship registration requests out of a total of 66 have been rejected, the flag said. Last year, 148 vessels were turned down.

And since 2020, more than 200 ships have been deregistered for reasons including suspicion of “illicit activities” or breaking sanctions imposed by the United Nations, the US and the European Union.

Tackling transition

The US Department of State is helping the ISRT avoid the flagging of some vessels that are sanctioned for calling at Iranian or North Korean ports.

The flag is also working with the EU, US and Spain to detect vessels that are involved in drug trafficking.

“We are pleased to have detected two vessels during January [that] both loaded this poison from Colombia with direction Europe or the Middle East,” the flag

said.

“We will continue our cooperation with ITF in all aspects, as we care also about the seafarers serving on board of our ships but also taking into consideration the position or opinion of the owners/managers when such unfortunate events

occur,” Medawar said.

Paul Sobba Massaquoi, executive director of the Sierra Leone Maritime Administration (SLMA), reacted with “dismay” at being included in the campaign.

“The Sierra Leone flag registry continues to uphold and work towards all its international standards for its vessels,” he said.

Most of its ships either move from or leave for the Panama, Greece, Liberia, Malta, Hong Kong and China flags, the SLMA added.

“Since 2020, Sierra Leone has only had 47 cases of MLC [Maritime Labour Convention] complaint and Sierra Leone flag has been replying to every single case that was reported,” Sobba Massaquoi said.

“From these 47 cases, 40 were successfully closed, meaning 89% of the cases, considering [that] two of these cases were for vessels not under Sierra Leone flag.”

Professional registry

The SLMA also pointed out that Algeria is on the Paris MOU black list, with Sierra Leone having a significantly better performance.

“We are an open and very professional ship registry and we have an open-door policy for any information,” Sobba Massaquoi said.

“We are all hoping that in future, the ITF should be supporting efforts of flags to improve and not the contrary, thereby trying to jeopardise and mislead the maritime industry into believing false and damaging information published about

a country’s flagship.”

The MLC will be coming into force after being ratified by the government of Sierra Leone in March 2022.

The Palau International Ship Registry (PISR) said statistical evidence presented by the ITF to justify its “unwarranted attack” is “wholly inaccurate, misinterpreted and therefore clearly misleading.”

“The negative picture presented of PISR is misguided, as any objective observer with maritime knowledge will understand,” it added.

In a spirit of constructive dialogue, chief executive Panos Kirnidis is suggesting a meeting with the union to advance seafarer safety.

The register has taken immediate action to address all cases brought to it to benefit seafarers’ rights under the MLC, the PISR added.

It said the International Labour Organization’s official abandonment database shows that PISR swiftly addressed and officially resolved all abandonment

issues.

The flag had only nine detentions out of 162 inspections in the last Paris MOU report.

For consecutive years it has been in the top third tier of the grey list at the Paris and Tokyo MOUs, the registry added.

The ITF has been contacted for further comment.

地中海で運航されているクック諸島船籍、 ![]() パラオ籍船、

パラオ籍船、 シエラレオネ籍船、

シエラレオネ籍船、![]() トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われるそうだ。これらの国籍の海運局は船主からお金さえ受け取れば、他の国籍の海運局が受け入れない船でも登録すると書かれている。これらの船籍船舶は危険で運航されるべきでないITFコーディネーターは言っている。データによると2年間でこれらの船籍に登録された100隻以上の船が放置されたそうだ。

トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われるそうだ。これらの国籍の海運局は船主からお金さえ受け取れば、他の国籍の海運局が受け入れない船でも登録すると書かれている。これらの船籍船舶は危険で運航されるべきでないITFコーディネーターは言っている。データによると2年間でこれらの船籍に登録された100隻以上の船が放置されたそうだ。

日本だと シエラレオネ籍船、

シエラレオネ籍船、![]() トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶が日本に頻繁に入港している。個人的には問題のある船は多いと思うが、

残念ながら日本のPSC(国土交通省職員)の検査は厳しくないので、出港停止命令はあまり受けないのが現状だと思う。

トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶が日本に頻繁に入港している。個人的には問題のある船は多いと思うが、

残念ながら日本のPSC(国土交通省職員)の検査は厳しくないので、出港停止命令はあまり受けないのが現状だと思う。

Sam Chambers

Up to 1,000 ships flagged to the Cook Islands, Palau, Sierra Leone, and Togo will be targeted for safety, maintenance and seafarer welfare inspections across the Mediterranean Sea in the coming eight weeks by an army of inspectors from the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), seafarers’ unions and port authorities.

“Substandard shipping in the Mediterranean Sea is driving down seafarers’ wages and conditions, it’s endangering the lives of crew and risking our environment,” said ITF inspectorate coordinator Steve Trowsdale.

“These flags take money from shipowners to register ships that other countries wouldn’t touch. Many are old vessels and are poorly maintained by their owners. Many of these ships are dangerous and should not be trading,” he said.

The blitz comes off the back of new analysis showing the four flags of convenience registries together accounted for more than 100 crew abandoned in the last two years, with millions of dollars wages not paid to crew by the flags’ shipowners that the ITF then had to recover on seafarers’ behalf.

The ITF inspectors’ efforts will be bolstered in France by the country’s Port State Control agencies, which are organised regionally.

By Eric Priante Martin

You would be hard-pressed to find a shipping register with as ignoble an inspection record as that of Cameroon. And yet, as TradeWinds correspondent Adam Corbett reports, nearly a year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine touched off a whirlwind of sanctions, ships are flocking to the registry and other marginalised flags as a “dark fleet” grows to move Russia’s energy exports.

The growth of flags with unenviable inspection records to serve a shadow tanker market is one of many yawning cracks that have emerged in shipping’s international regulatory framework in the wake of the conflict in Ukraine.

It is a global structure that relies on the willingness of flag states and port states to regulate and inspect. That has left a door open for ships to enter a dangerous realm, as long as they trade where both flag and port state will look the other way.

Trading giant Trafigura has estimated that some 600 ships are operating in the dark fleet, including 400 crude tankers, according to Bloomberg.

Shipping’s safety record has improved on many fronts over the years, and thankfully oil spills are a relatively rare event. But companies operating in the dark trades are brazenly flouting the provisions of the international safety regime, bulldozing through regulatory norms by turning off AIS transponders, engaging in offshore ship-to-ship transfers and carrying out other deceptive practices.

The fact vessels are flocking to registries that will hold them to a lower standard to play this game is another concerning development in the growth of the dark fleet serving Russia.

Gabon and Tanzania

Among those are Gabon, whose fleet barely registers in port-state-control data, and Tanzania, which the US Coast Guard has labelled a high-risk flag.

In the case of Cameroon, the fleet under the country’s flag surged by 41.5% in 2022, as TradeWinds reports.

The Paris Memorandum of Understanding, a treaty organisation that tracks port-state detentions, has the country listed at the very bottom of its black list and has labelled it as the only “high risk” shipping flag. That was based on data from 2019 to 2021, when 21.7% of 69 inspections resulted in a ship being detained.

There is no indication that its record has got any better.

In fact, although the Paris MOU has yet to reveal its latest blacklist, a TradeWinds review of its data shows the detention rate for 2022 only got worse, with 26.6% of inspections of Cameroon-flagged vessels resulting in the ship being held, lifting the three-year average that will decide whether it stays on the black list to 23.7%.

90% of ships with deficiencies

A vessel flying Cameroon’s flag can barely make it through an inspection without authorities finding a safety problem. After all, more than 90% of inspections found at least one deficiency in 2022, the Paris MOU database shows.

Dark activities by Cameroon-flagged tankers in the South Atlantic increased from seven events in 2021 to 315 in 2022, according to data analysis firm Windward. Cameroon’s transport ministry did not immediately respond to TradeWinds’ request for comment on the information.

Windward pointed to one ship as an example of the deceptive practices underway in shipping.

The outfit reported that after switching to Cameroon’s flag in July, the 45,200-dwt product tanker Nobel (built 1997) engaged in a number of suspicious activities, including loitering in locations with no commercial or economic reason, location data manipulation and ship-to-ship transfers.

One of those transfers led Spanish authorities to bar Maersk Tankers’ 50,000-dwt Maersk Magellan (built 2010) from unloading at the port of Tarragona, but another ship appears to have carried a smuggled Russian cargo from the Nobel to the Spanish port of Ferrol.

But worrying from a safety perspective is that during all of this activity, the Nobel was under questionable oversight. (Its current owner — a Seychelles-registered company with no other ships to its name — could not be reached for this story.)

When the vessel was sold in July, it moved to the Cameroon registry from the Russian Maritime Register of Shipping, which was also its classification society at the time and is historically among the better-performing shipping flags.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is showing shipping companies that want to operate outside of the international regulatory order will still find a home.

They may be welcomed with a flag of convenience that, with little regulatory oversight, will also take ships on the fringes of the global safety regime.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) specifies that all ships “have the nationality of the State whose flag they are entitled to fly.” Consequently, flag states exercise jurisdiction over their flagged vessels. A recent and quickly growing phenomenon, however, has put this basic tenet of the law of the sea in question: unauthorized flag use.

Unauthorized flag use is a practice whereby a vessel uses a state’s flag without its consent and, oftentimes, without its knowledge. Although this can take many forms, often overlapping, it may be helpful to think of this issue in two broad categories: fraudulent flagging and false flagging. Fraudulent flagging generally entails an official recognition of fraudulent registration, e.g. fraudulently issued registration documents resulting in formal recognition by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). False flagging, on the other hand, describes a situation where a vessel falsely claims registration different than the flag it is actually authorized to fly as a matter of expediency. Both create a gap wherein there is no effective oversight of the vessel’s activities, which can be exploited to facilitate a range of illicit activities.

Fraudulent Flags, Real Issues

The issue of fraudulent flagging was brought to the attention of the international community in 2015, when the IMO became aware of a fraudulent registry purporting to operate on behalf of the Federated States of Micronesia. Micronesia does not operate an international shipping registry. It is not even an IMO Member State. Two years later, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) formally brought the issue to the attention of the IMO Legal Committee after discovering that 77 out of the 84 vessels flying its flag have been doing so without authorization. Other countries have also fallen victim to fraudulent registration, including Fiji, Samoa, Nauru, Vanuatu and the Maldives. Although in some cases, like Nauru, the fraud was caught early enough that no fraudulent documents were ever issued, as of last year over 300 vessels are believed to have been registered fraudulently.

These fraudulent registrations are exploited by those engaged in illicit activity. In the case of the DRC, the country only became aware of the issue when contacted by INTERPOL with a request to prosecute two vessels engaged in illicit activity that claimed the DRC flag. Of the 98 vessels investigated by Fiji since 2017 for fraudulently claiming its flag at least 20 percent were subsequently linked to North Korea and likely engaged in sanctions evasion. Fraudulent registries not only deprive legitimate registries of income but can also cause significant reputational damage when vessels fraudulently flying a flag are involved in illicit activities. In just one example, the Maldives found itself having to officially deny a statement by the Japanese Foreign Ministry which identified a supposedly Maldives-flagged vessel as engaging in a prohibited ship-to-ship transfer with a North Korean tanker.

In addition to enabling illicit activity and causing financial or reputational damage to legitimate maritime actors, fraudulent and false flagging can also adversely impact a range of other areas—maritime safety and security, environmental protection, and maritime emergencies among them. More broadly, as the resolution on the subject adopted by the IMO Assembly in January 2020 notes, unauthorized flag use “endanger[s] the integrity of maritime transport, and undermine[s] the legal foundation of the Organization’s treaty and regulatory regime.”

Despite that, the IMO response to the issue has been slow to come. While the organization has been aware of the problem at least since 2015, it was only in 2019 that it adopted any concrete measures to address it. One of these measures involved establishing a whitelist of authorized national registries and a procedure of verifying the information provided. This is particularly important given that the IMO had in the past erroneously recognized the fraudulent Micronesia International Ship Registry as a legitimate authorized body acting on behalf of the Micronesian government.

The other element—perhaps the most practically impactful—is the adoption of a new flag indicator in IMO records denoting fraudulent registrations. Adopted as an outcome of the March 2019 meeting of the IMO Legal Committee, it is intended to identify instances where a flag state has confirmed that a vessel was never legitimately registered. This, however, has been implemented inconsistently and likely only identifies a portion of vessels that have engaged in the practice. As an example, despite Micronesia having never operated a flag registry, not all vessels which had fraudulently claimed Micronesian registration are marked with the ‘false’ indicator in the IMO’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS).

While these steps are welcome, they are insufficient to combat fraudulent flagging on their own. Indeed, the most impactful measure taken has been efforts by individual countries to denounce fraudulent registrations issued in their name. Marine circulars by Tuvalu and the Cook Islands note that Fiji reported the unauthorized use of its flag to the Tokyo MOU while Micronesia, Nauru, and Samoa reported the fake registries operating in their name to the IMO. Notifying multilateral organizations of the issue may have contributed to decreased unauthorized use of these countries’ flags: an annual report on vessel inspections maintained by the Tokyo MOU shows drastic decreases in inspections of vessels flagged to both Fiji and Micronesia between 2017 and 2019. Inspections of vessels “registered” to Fiji went from 23 to four; those for Micronesia from 67 to zero.

False Flagging – Quicker and Easier

In comparison to the relative success combatting fraudulent flagging, false flagging poses a more complex challenge. This is because it is much easier to perpetrate: it does not require anchoring the deception in an official recognition by the IMO, but instead involves creating a false identity that is good enough to get away with illicit activity in the present moment. This includes broadcasting false identities via a vessel’s Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponder—a safety and navigation system whose use for most international vessels is mandated by International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)—or the fraudulent use of registration documents.

Broadcasting false identities using AIS transmissions is relatively straightforward as the identifiers broadcast are entered manually. This allows them to be changed frequently, complicating efforts to track a vessel’s activities. AIS transmissions using identifiers registered to the KUM RUNG 5, a North Korean cargo ship, for instance, show a vessel cycling through around 30 different identifiers, including names, Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) numbers, callsigns, and even IMO numbers, which are meant to be unique to just one vessel throughout its lifetime. This includes the use of at least four names in 2020 alone. Because the identifiers are programmed onboard the vessel, confirming the authenticity of the broadcast is not possible without other means of verification.

A vessel seeking to falsify an identity can also match the unique identifiers legitimately assigned to another vessel. In the case of a North Korea-flagged cargo vessel TAE YANG, investigated jointly by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies and the Royal United Services Institute, the vessel mimicked aspects of the identity of the Mongolia-flagged tanker KRYSPER SINGA. The AIS record initially broadcast by the TAE YANG with its assumed identity appeared to show the KRYSPER SINGA as having visited North Korea, while the real KRYSPER SINGA was actually off the coast of Singapore. Imagery, both satellite and ground, was necessary to verify that the AIS transmissions from North Korea were really coming from another vessel, the TAE YANG. Relying on AIS transmissions alone would have implicated an otherwise innocent vessel in a violation of United Nations sanctions on North Korea.

With regards to the use of fraudulent documents, the somewhat artificial distinction between fraudulent flagging and false flagging blurs. But a distinction, however minute, remains: fraudulent documents in the context of false flagging are used not to support a registration claim made to the IMO but to allow a vessel to navigate interactions with third parties when expedient. The case of the WISE HONEST is illustrative.

The WISE HONEST was a bulk carrier detained by Indonesia in 2018 for illicitly exporting coal from North Korea. At the time of the detention, it was registered to North Korea. Yet court documents show that the vessel initially identified itself to Indonesian authorities as being flagged by Sierra Leone—which it had been from August 2015 until May 2016. Authorities found two sets of documents onboard the vessel, one supporting registration with Sierra Leone, and one with North Korea. Although it is unclear whether the Sierra Leone documents found on the WISE HONEST in 2018 were an expired set of documents issued to the vessel in 2015 or a forgery, this case illustrates the ease with which legitimately issued documentation could be repurposed for illicit activity.

Building a Better Response

Although the measures adopted by the IMO are an important step toward addressing the problem of fraudulent and false flagging, a much more comprehensive response is needed. This should combine measures taken collectively by the appropriate international bodies, measures taken individually by states, and measures taken by the private sector.

At the international level, leadership by the IMO is crucial. Actions taken to date have been slow and limited in nature, largely hewing to IMO’s traditionally defined role. In addition to the two measures described above, the IMO has also issued a guidance on best practices to combat what it terms “fraudulent registration and fraudulent registries of ships.” The guidance urges states to make use of the registry whitelist and ‘false’ indicators in GISIS, verify the vessel’s IMO numbers and Continuous Synopsis Record prior to registration, and consult the UN sanctions lists. This guidance, however, does not go far enough. It does not seem to, for instance, address false flagging—the unauthorized use of a country’s flag absent fraudulent registration. Action to rectify this ought to include facilitating information sharing on vessels engaged in false flagging with the aim of allowing countries to better coordinate vessel de-registrations, detentions, and prosecutions, where applicable. Given IMO’s statutory functions, this naturally falls within the organization’s areas of responsibility.

At the national level, there are several steps countries can take.

First, implement national measures to prosecute fraudulent or false flagging and the illicit activity it facilitates, and enhance enforcement capabilities. Though fraudulent or false flagging may be illegal in some jurisdictions, this has not deterred vessels from engaging in the practice. This might have to do with how difficult enforcement action can be. Fiji opened criminal investigations into the unauthorized use of its flag in 2017. Its current status is unknown. Micronesia was finally able to bring charges in April 2020 against the individuals behind the Micronesia International Ship Registry—five years after the fraudulent registry first became active. Following the detention of the WISE HONEST in 2018, the only charges Indonesia could bring against the captain of the vessel were for “being in charge of an unseaworthy vessel.” It is unclear whether Sierra Leone tried, or would have been able to take any action in relation to unauthorized flag use.

Prosecution on the basis of the associated illicit activities—violations of United Nations sanctions on North Korea, for instance—could offer a supplemental pathway as well. Yet all too often, these measures are not appropriately implemented in national legislation. In many, if not most, cases, however, mutual legal assistance agreements would likely be necessary to take action effectively, given that vessels claiming a flag fraudulently may never be under the aggrieved party’s effective jurisdiction. The same is true of appropriate national enforcement procedures, without which any enforcement action will be difficult if not impossible. Exercises like those conducted under the banner of the Proliferation Security Initiative— a multinational response to the transnational threat of the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction—could focus on the ability to track and interdict a shipment and help build this capacity.

Second, invest in capabilities to monitor a broader set of vessel activity. In order to follow through on national legislation criminalizing fraudulent or false flagging, countries need to be able to identify it. Doing so requires investment in capabilities—both human and technological—to monitor vessel activity. Human capabilities entail relevant personnel knowing how to identify vessels engaged in fraudulent or false flagging. This is key to making sure that indicators of fraudulent or false flagging are noted and acted upon. Technological capabilities include the ability, likely via an AIS monitoring platform, to trace AIS transmissions linked to vessels in a country’s territorial waters to see if they have previously engaged in fraudulent or false flagging, and the ability to scan for AIS transmissions making unauthorized use of the country’s flag. Regional partnerships may offer smaller states, including those without international ship registries, a more cost-effective way of maintaining these capabilities.

Third, when it comes to assumed identities and identity theft perpetrated through AIS transmission, the way AIS transponders work is part of the problem: manual data entry makes fraud quite easy. The most recent advisory for the maritime sector issued by the U.S. government recommends that registry managers work with classification societies to provide a “soft lock” on AIS transponders, which would disable the option of manual changes during a vessel’s voyage while allowing for disablement in sanctioned emergency situations. This could go some way toward addressing the issue, although it would necessarily miss many of those actors already engaged in illicit activities who are not likely to allow for this sort of modification to their vessel’s equipment.

The private sector also has a role to play. To do so, it is important that AIS data providers and AIS monitoring platforms review how they aggregate data associated with false flagging. The ability of states to take action against those engaged in fraudulent or false flagging is contingent on the indicators of that practice being visible. As noted in the report on the TAE YANG, AIS data can be “corrected” or jettisoned when found to be associated with a vessel identity not registered with the IMO. This risks, in effect, erasing the illicit activity or making it harder to attribute. In the case of the TAE YANG, its AIS transmissions were merged with those of the KRYSPER SINGA and ultimately attributed to it. In other cases, like that of the KUM RUNG 5, AIS data for what is likely a single vessel may be grouped into different records on the basis of some of the false identifiers used by a vessel engaged in false flagging. Failure of data providers and maritime platforms to address these issues risks undermining faith in AIS as a means of monitoring vessel identities and activities—leaving national authorities and independent analysts with one fewer tool to monitor and disrupt illicit activity.

Conclusion

Fraudulent and false flagging is a complex issue requiring action from multilateral organizations like the IMO, national authorities, and the private sector. Each of these actors has a different set of incentives. Much is at stake for the private sector, including both data providers and the maritime industry that uses said data, and the reliability of AIS transmissions. For individual countries, their motivation comes from the reputational or financial costs they might incur as victims of unauthorized flag use. And for the international community writ large, with the IMO as the guardian of global maritime trade, the persistent and seemingly growing problem posed by fraudulent and false flagging—as the organization itself admits—threatens to undermine the entire legal regime it embodies. The temptation to pass responsibility for combatting unauthorized flag use to others is immense. But it is only through steps taken collectively by all relevant stakeholders that this problem can be addressed.

Source: CIMSEC

パナマ・リベリア・マーシャル諸島船籍が世界の約4割

船舶に関する報道で、中米の「パナマ船籍」と聞くことが多い気がします。ただ、乗組員は他国人であっても、船籍はなぜか「パナマ」というケースも。どういうことなのでしょうか。

【地図】パナマってどこ? おもな「便宜置籍国」

「当社の船もパナマ籍が多いですね」と話すのは、日本最大手の海運会社である日本郵船の担当者です。日本、そして世界の海運会社が、船籍を自国ではなく、あえてパナマなどに置いているケースがあるといいます。世界的な海運の動きをまとめた日本海事広報協会(東京都千代田区)の年報「SHIPPING NOW 2017-2018」によると、世界の船舶はパナマ籍が最も多く17.7%、日本の外航海運会社が運行する船では、パナマ籍がじつに61.3%を占めます。なぜ、わざわざ他国に船籍を置くのでしょうか。

このように、ある国の会社が船籍を他国に置くことを「便宜置籍」といいます。海運の業界団体である日本船主協会のウェブサイトではその理由について、「船にも人間と同じように国籍があり、登録した国の法律によって制約と保護を受ける。しかし、その内容は国によってまちまち。そこで、より有利な条件を持つ国に便宜的に船籍を移す動きが、戦後、世界の海運国で活発になった」とし、このような登録ができる「便宜置籍国」のひとつにパナマを挙げます。

ちなみに、前出の海事広報協会「SHIPPING NOW 2017-2018」によると、世界の船舶はパナマ(17.7%)に次いで西アフリカのリベリア籍が11.1%、3位がオセアニアのマーシャル諸島共和国籍で10.6%となっています。日本の外航海運会社が運行する船では、パナマ籍(61.3%)に次いで日本籍が9.1%、リベリア籍が5.7%だそうです。

「便宜置籍」なぜ行われる?

日本郵船に、便宜置籍を行う理由について聞きました。

――なぜ便宜置籍を行うのでしょうか?

まず船舶登録が容易かつ安価に行えます。船主となる会社をその国に設立し、その管理や解散も容易であるほか、外国人船員の配乗も容易です。

――便宜置籍はいつごろから行われているのでしょうか?

日本においては、本格的に便宜置籍国への登録が増え始めたのは1970年代です。1971(昭和46)年のニクソンショック以降、為替相場が円高に振れたことから、競争力確保のためコストの「ドル化」を進めたのがきっかけです。

※ ※ ※

前出の日本船主協会ウェブサイトでは、「日本を含め、ほとんどの先進海運国では、自国の船には、原則的に自国人や自国が承認する海技免状等を持った船員の乗船を義務づけている。しかし先進諸国の船員は賃金も高く、より低賃金の発展途上国海運との価格競争では不利。一方、便宜置籍国では、こうした国籍要件等に関する規制が緩やかで、賃金の安い外国人船員を乗せることができる」といった便宜置籍のメリットを挙げています。

これに加え、日本郵船は「為替リスクの軽減」も挙げます。「決算通貨を選択できるので、コストをドル化するといったことが可能です。政治的な理由などで一国の通貨が変動する事態にも対応できます」と話します。

一方、便宜置籍には法人税などの節税対策という側面もあるのでしょうか。日本郵船によると、「日本では外国子会社合算税制(いわゆるタックスヘイブン対策税制)があり、租税に関するメリットは特にありません」とのことです。

「日本船籍」復活の動きも

このように昔から行われてきた便宜置籍ですが、最近は日本籍の船も増えているそうです。日本郵船は次のように話します。

「外航海運は『世界単一市場』で厳しい競争に勝ち抜く必要があり、便宜置籍国への船籍登録は今後も継続していくと考えられます。一方、安定的な海上輸送の確保という観点から、日本の外航船舶運航事業者が国際的な競争力を確保しつつ、日本船舶および日本人船員の計画的な増加を図ることも重要な課題です。外航海運に対する課税の特例である『トン数標準税制』が2008(平成20)年に導入されていることから、日本籍船も今後増加させていく予定です」(日本郵船)

「トン数標準税制」とは、実際の利益に応じてではなく、船舶の大きさを基準として、一定かつ低水準の「みなし益」を設定して課税する制度です。適用を受ける事業者は、日本籍の船や日本人船員を増やす目標を明記した「日本船舶・船員確保計画」を作成し、国土交通大臣の認定を受ける必要があります。1970年代以来減少し続けていた日本の外航海運会社における日本籍船の割合は、この制度が導入された2008(平成20)年から増加に転じ、8年間で3.7%から9.1%まで上昇しています。

一方で日本郵船によると、便宜置籍国はビジネスとして自国籍船の誘致を行っており、特にパナマ、リベリア、マーシャル諸島が力を入れているとのこと。「コスト面のみならず、サービスの充実に各国ともしのぎを削っているような状況です」と話します。また、便宜置籍はクルーズ船など旅客船でも行われ、特にカリブ海の諸島国であるバハマ籍が多いようだといいます。

乗りものニュース編集部

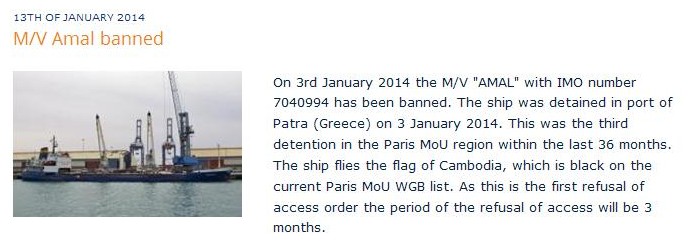

例外がある。 カンボジア船籍船だ。

カンボジア船籍船だ。

カンボジア政府及び韓国の船舶登録会社は国際条約を守るのは船主の責務であると発言した。誰も責任を取らないのだから、サブ・スタンダード船の隻数が世界でナンバー1になるのだろう。改善する姿勢が見られなければカンボジア船籍船を入港禁止にしても良いだろう。ヨーロッパではArticle 16に従い、入港停止にされたカンボジア船籍船が存在する。

旗国の多くが財政的に問題がある国や小国である。目的は、外貨獲得である。 (例1) この事自体は、問題があるとは思わない。しかし、監督(管理)に問題がある場合、 サブ・スタンダード船 問題に深く関係することになるのである。

Sierra Leone has taken a global lead in tackling illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing by closing its shipping registry to foreign-owned fishing vessels.

Speaking in Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown today, Fisheries Minister Joseph Koroma announced that the cabinet had unanimously agreed to close the Sierra Leone international ships registry to foreign owned fishing vessels, effectively banning the sale of so-called ‘Flags of Convenience’, used by pirate fishing operators to disguise their activities.

‘We are very proud to be the very first nation to take this extremely important step in our efforts to combat IUU fishing,’ said Koroma.

By KaranC Maritime Law

Every merchant ship needs to be registered to a state of its choice. The ship is then bound to carry the flag of that state and also follow the rules and regulations enforced by the same. The ship’s flag is an important factor when the court makes the decision on the judging.

The ship will follow the regulation of the flag state nation’s maritime law in the open sea and it will also avail different protections and preferential treatments as tax, certification, and security etc as per the flag state benefits.

Ship registration plays an important role in many aspects such as vessel purchases, newbuilding deliveries, financing, vessel leasing, and different priorities of owners and mortgagees.

Why Flag State?

The term Flag State came to existence because of the usage of flags as the symbol of the nationality or tribe the ships belong to from the early days. The flag has come to be an officially sanctioned and very powerful symbol of the State and is the visible evidence of the nationality conferred by the State upon ships registered under its national law. The ship’s flag displays the nationality of the ship, under whose laws the ship is plying in the international waters.

However, it is to note that not all vessels are registered to their ship owners’ country of origin. The country under whose registration such vessels operate is referred to as a flag state whereas the practice of registering the ship to a state different than that of the ship’s owner is known as the flag of convenience (FOC).

The vessel in consideration thus has to comply with all the maritime rules, regulations and stipulations laid out by the flag state in accordance with the international maritime rules and stipulations.

For a country to be included in the list of flag states, it has to have the necessary maritime infrastructure – both financial and technical and should, most importantly, adhere to all the norms and regulations established by the International Maritime Organisations (IMO).

Additionally, in case a ship is not complying with the required norms imposed by authority, then the country registered as a flag state needs to be adequately equipped to impose strictest of penalties on the offending vessel and party.

Although there are several benefits to have a separate flag state and register a vessel to its port of registry, there are several significations of the same as well.

地中海で運航されているクック諸島船籍、 ![]() パラオ籍船、

パラオ籍船、 シエラレオネ籍船、

シエラレオネ籍船、![]() トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われるそうだ。これらの国籍の海運局は船主からお金さえ受け取れば、他の国籍の海運局が受け入れない船でも登録すると書かれている。これらの船籍船舶は危険で運航されるべきでないITFコーディネーターは言っている。データによると2年間でこれらの船籍に登録された100隻以上の船が放置されたそうだ。

トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶をターゲットにして船舶検査が行われるそうだ。これらの国籍の海運局は船主からお金さえ受け取れば、他の国籍の海運局が受け入れない船でも登録すると書かれている。これらの船籍船舶は危険で運航されるべきでないITFコーディネーターは言っている。データによると2年間でこれらの船籍に登録された100隻以上の船が放置されたそうだ。

日本だと シエラレオネ籍船、

シエラレオネ籍船、![]() トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶が日本に頻繁に入港している。個人的には問題のある船は多いと思うが、

残念ながら日本のPSC(国土交通省職員)の検査は厳しくないので、出港停止命令はあまり受けないのが現状だと思う。

トーゴ籍船に登録されている船舶が日本に頻繁に入港している。個人的には問題のある船は多いと思うが、

残念ながら日本のPSC(国土交通省職員)の検査は厳しくないので、出港停止命令はあまり受けないのが現状だと思う。

Sam Chambers

Up to 1,000 ships flagged to the Cook Islands, Palau, Sierra Leone, and Togo will be targeted for safety, maintenance and seafarer welfare inspections across the Mediterranean Sea in the coming eight weeks by an army of inspectors from the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), seafarers’ unions and port authorities.

“Substandard shipping in the Mediterranean Sea is driving down seafarers’ wages and conditions, it’s endangering the lives of crew and risking our environment,” said ITF inspectorate coordinator Steve Trowsdale.

“These flags take money from shipowners to register ships that other countries wouldn’t touch. Many are old vessels and are poorly maintained by their owners. Many of these ships are dangerous and should not be trading,” he said.

The blitz comes off the back of new analysis showing the four flags of convenience registries together accounted for more than 100 crew abandoned in the last two years, with millions of dollars wages not paid to crew by the flags’ shipowners that the ITF then had to recover on seafarers’ behalf.

The ITF inspectors’ efforts will be bolstered in France by the country’s Port State Control agencies, which are organised regionally.

九州の門司でシエラレオネ籍船貨物から覚醒剤が見つかり船は2年近く放置された。 管理・監督が甘い旗国に登録にされている船舶で起こる確率が高い問題だ。

世界中に多くの証書を発行できる検査会社が存在する。 お互いにサービスの競争により、質の高いサービスを提供できれば良いが、 現実は、理想や理論とは違う。

カンボジア船籍船が増加する前は、ベリーズ船籍船が有名であった。参考資料のデータが古いが参考にしてほしい。

外航船インシデントと船籍についての現状分析 海上警察学講座 松本宏之 (海上保安大学校)

開けない人はここをクリック

パーセントではなく問題のある船舶の登録数で言えば、カンボジア籍船 がダントツで最悪だ。 UNDER-PERFORMING SHIPS (1年間に3回以上出港停止を受けた船舶) TOKYO MOUのHPによると カンボジア籍船は隻数でワースト1 。海難や船舶放置問題を見ても、カンボジア船籍船は日本でナンバー1だ。 TOKYO MOUエリアの PSC達が厳しい検査を徹底的に行い。 不備を是正するまで出港停止を繰り返し行い、頻繁に出港停止を受ける船舶の入港禁止を実行するまで問題は解決されないであろう。

監督や監査をする機能が働かない場合、検査をごまかす、見逃すことにより、顧客を 獲得出来る場合がある。 中央青山監査法人が関与したカネボウの粉飾事件 で解明された動機も参考になるだろう。処分が甘ければ、簡単なチェックの会社に仕事の依頼する傾向は高い。

旗国の中には自国の公務員が旗国の船舶を検査する場合もある。しかし、船舶が国内だけで 運航される場合は問題ないが、船は世界中の海を航海する。運営、コスト面及び人材などで名前を聞かれる旗国の多くは 民間の検査会社を承認し外部委託をしている。 承認する検査会社に問題がある場合、 サブ・スタンダード船 を生み出す環境が出来上がる。 問題のある検査会社を承認するような旗国は、 管理能力や管理できる人材不足などの問題を抱えているか、カンボジア政府のように安易な収入(クイックマネ-)のために妥協したと考えて間違いないだろう。自浄能力(コトバンク) は働かないとかと思う人もいるであろう。 例としてあげるなら、カンボジア籍船であろう。カンボジア船籍船に関する一切の権限は韓国の会社(ISROC)に6百万UDドルで売られたそうだ。欧州委員会(E.C.)に対してカンボジア政府はカンボジア船籍船の問題について「韓国の船舶登録会社に責任がある。」と発言している。 韓国の船舶登録会社は「国際条約を守るのは船主の責任」と無責任な発言をしている。結局、このような考え方や対応を取る組織や人々が存在するので法律や規則が必要になる。法律や規則がなければ、やったもの勝ちになる。

世界の多くの国々と比較して経済的に安定し、治安の良い日本でも 警察の不祥事はなかなか改善できない。経済的にゆとりのない国ではなおさらだ。 自浄能力(コトバンク) は期待できないし、期待しない前提で対応するほかはない。

一般的に、それぞれのMOUやPSCのデーターから判断すると、 国際船級協会連合(IACS) のメンバーだけを検査機関として承認している旗国は、メンバー以外の検査機関を承認して いる旗国よりも、出港停止命令及び不備を指摘される項目が少ない。

何故なのか? 国際船級協会連合(IACS) のメンバーでない検査会社の質が低いからである。問題のあるメンバー以外の検査会社を、以後、 サブROと呼ぶ。サブROを調べていくと、問題のある旗国と呼ばれる国々から承認を受けているケースが高い。

サブROと問題のある旗国は、PSCの出港停止命令を受けた船舶のデーターの掲載される共通の 問題点がある。ここで、問題のあるサブROを承認する、又は、処分を下さない国にも責任がある。 そして、 問題船を検査し、問題があるにも関わらず、証書を発給する検査会社 に サブ・スタンダード船 の原因があることがわかる。

悪質な船舶所有者や船舶運航者はずる賢い。 監督(管理)ができない国(旗国)に 船舶を登録する。登録により、国(旗国)は登録料及びその他の費用により外貨を獲得する。 監督を怠り、お金儲けに走れば、問題のある船舶ばかりがある特定の国に登録される ようになる。監督を怠ると言うことは、 適切に検査をおこなっていない検査会社 への委任の取消し処分を行わない事、船舶登録時に事前検査システムがある場合、事前検査を行わずに登録させたり、 適切に検査をおこなわない検査官を承認する事等のことである。また、船員が十分な教育や訓練を受けていないのに免状を 発給する問題も監督の怠慢となろう。これは、操船ミスによる海難事故や座礁事故の原因となる。 仮国籍証書だけで航行する船舶もある。船舶は国際条約で国際航海に必要な証書が要求される。しかし、通関に関しては 仮国籍証書と国際トン数証書があれば問題ない。そこで、仮国籍証書だけで航行する船舶もいるのだ。特に、内航船が海外の買い手 に売られて日本から出航する時に、国際条約で要求される証書を持っていないので、仮国籍証書だけの場合が多いようである。 これらの船舶が最低限の安全装備や刊行物を備え、 十分な 資格を持った船員が乗船し、航海することの確認をしないことも監督の怠慢と言えるだろう。 口コミやうわさで、他の国(旗国)に登録出来ない船舶や検査会社の 問題の指摘を受け運航できない船舶の所有者が登録するのである。そして、結果的に ブラック・リストに国(旗国)の名前が載るのである。

韓国船籍はブラックリストに載るほどひどい国籍ではない。しかしながら、 韓国船籍旅客船「セウォル号」(M/V"SEWOL", IMO9105205)の事故の原因と事故に至るまで過程を見ると酷いと思う人もいるでしょう。 ブラック・リストに国(旗国)の名前が載る国籍の船はもっとひどいと考えて方が良い。カンボジアが良い例だ。カンボジア船籍船の問題についてカンボジア政府は責任がなく、韓国の船舶登録会社に責任があると発言する。国際条約を守るのは船主の責任と責任回避する船舶登録会社。

韓国船籍旅客船「セウォル号」(M/V"SEWOL", IMO9105205)の事故の場合は、隠れサブ・スタンダード船が含まれている事が明らかになった。その原因は、旗国と船級の癒着、モラルの無い船主及び/又は船舶運航会社、政府から委任されている第三者機関の癒着と怠慢等であった。そして結果として、監督システムは存在するが旗国(韓国)によるコントロールが機能していない状態になっていた。多くのサブ・スタンダード船が登録されている旗国では、同様に監督システム(フラッグ・インスペクション)が建前では存在するが、韓国船籍旅客船「セウォル号」(M/V"SEWOL", IMO9105205)の問題を指摘できるように機能していない。今回の惨事は多くの犠牲者が出たために形だけの調査ではなく、ある程度の調査が行われ、英語や日本語の記事として取り上げられた。船員が死亡しただけの事故であれば、ここまで注目も受けなかったし、ここまで原因が公表されなかったし、多くの逮捕者が出なかった。

韓国船籍旅客船「セウォル号」(M/V"SEWOL", IMO9105205)の事故はなぜ ブラック・リストに国(旗国)の名前が載る旗国の船舶は事故を起こしやすいのかを説明する良い例になったと思う。旗国と船級の癒着、モラルの無い船主及び/又は船舶運航会社、政府から委任されている第三者機関の癒着と怠慢等の関係がここまで明らかになる事は今後無いかもしれない。

現在でも、 新たな国(旗国) (例1) (例2) が誕生している。 世界規模で サブ・スタンダード船 の取締りがさらに厳しくなれば、 良い船舶所有者が選んでくれる国(旗国)以外は生き残れないだろう。 しかし、現状は、違反船や問題船が自由に航行でき、悪いイメージが持たれている国(旗国) が改善しようと思っても、悪質な船舶所有者は他の悪い国(旗国)に変わるだけある。 新しい国(旗国)が、ブラック・リストに載せられるだけである。そして、非難される。 PSCが法の番人、 秩序の保守のために活動しない限り、問題の解決にならない。 残念ながら国によってはPSC(外国船舶監督)の腐敗(賄賂) の問題や簡単な検査しか行わない(出来ない)PSC(外国船舶監督) も存在する。よってサブ・スタンダード船はなかなか減少しない。

「年間約2万5千件の外国船検査の内、約5千件は日本が実施しており、これを行う外国船舶監督官を今年度全国で142 名予定と するなど取組み強化を行っています。」平成24年4月20日 (国土交通省のHPより)

「欠陥を抱えるリスクの高い約3割の外国船を優先して繰返し検査する方針」としているが、優先に検査しても不備を見つける能力とやる気がある PSC(外国船舶監督)が不足していれば名前だけのPSC(外国船舶監督) では結果は期待できない。 出港停止を受けた船舶 TOKYO MOUのHPよりを見ていただければ理解できると思うが、船舶が特定の港(エリア)でしか出港停止命令を受けていない。 これはサブ・スタンダード船が特定の港(エリア)しか入港しているわけではなく、 特定のPSC(外国船舶監督)しか、不備を見つけ出港停止命令出していないのである。

このような現状を理解してから「外国船舶監督官を今年度全国で142 名予定」の記事を誤解して理解することとなる。 結果が出ないからPSC(外国船舶監督)のならなる増員は仕方がないと 思っていると税金の無駄遣いを容認することとなる。日本政府が許している税金の無駄遣いが他の省庁でもたくさんある理由はこのように問題点が あると個人的に思っている。

フィリピン船籍は便宜置籍船(FOC)ではないが、2023年に沈没し、油汚染をひきおこしたタンカー船「PRINCESS EMPRESS」の書類が偽造で使われたいた名前の職員は船が建造されたとする年の2年前に退職し、建造された年に死亡していた。フィリピン沿岸警備隊職員による検査を沈没前に4度受けたようだが、問題は発見されなかった。このように検査システムがしっかりしていないと問題が見逃される事は便宜置籍船(FOC)に限った事ではないと言う事だと思う。

便宜置籍船(FOC) 隠れ場所などどこにもない (国際運輸労連) と書かれているが、隠れる場所はたくさんある。

モンゴル船籍船が売船され日本の港から出港し、沖縄で座礁し放置されている。このような問題を海上保安庁は知っていながら、

売船されたモンゴル船籍の自動車運搬船「HARMONIMAS3」を尾道から簡単に出港させている。

その後、どうなったのか?奄美大島沖で機関故障のため、航行不能となった。学習能力が欠如しているのか、口だけだと思う。

そして、外国船舶監督官(PSC)達も問題のある船を検査して、問題を指摘しない。これでは隠れ場所などないどころではなく、隠れ場所はたくさんあるだ。

モンゴル船籍船が売船され日本の港から出港し、沖縄で座礁し放置されている。このような問題を海上保安庁は知っていながら、

売船されたモンゴル船籍の自動車運搬船「HARMONIMAS3」を尾道から簡単に出港させている。

その後、どうなったのか?奄美大島沖で機関故障のため、航行不能となった。学習能力が欠如しているのか、口だけだと思う。

そして、外国船舶監督官(PSC)達も問題のある船を検査して、問題を指摘しない。これでは隠れ場所などないどころではなく、隠れ場所はたくさんあるだ。

【ソウル聯合ニュース】アジア太平洋地域で船舶への検査をモニタリングする国際組織「東京MOU」の最新報告書によると、2020年に安全検査を実施した北朝鮮の船舶13隻すべてから1件以上の欠陥が見つかった。このうち、2隻については問題解決まで船舶の運航を中止とする停船措置を出した。

また、北朝鮮をブラックリストに掲載し、北朝鮮船舶に対し、他国より高い比率で安全検査を実施するようにした。

ブラックリストに掲載された国は北朝鮮のほか、トーゴ、シエラレオネ、モンゴル、ジャマイカ、パラオ、キリバスの7カ国。

北朝鮮船舶は大多数が火災安全や救助装備、非常システムの不備で検査をクリアできなかったという。経済難や制裁により老朽化した船舶を廃棄・修理できず、運用を続けるしかなかったためとみられる。

北朝鮮船舶に対する安全検査は2016年に275隻、17年に185隻、18年に79隻、19年に51隻と減り続け、昨年は新型コロナウイルスの影響で13隻まで落ち込んだ。

【ソウル=峯岸博】韓国の聯合ニュースは31日、北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いのあるパナマ船籍の石油タンカーを韓国当局が検査していると報じた。韓国西部の唐津港に留め置かれており、船員の大半が中国人とミャンマー人だという。

国連安全保障理事会は北朝鮮の核・ミサイル開発を封じ込めるため、石油精製品の輸出を規制する制裁を採択した。今回の船舶間の移し替えが事実なら、制裁逃れの韓国政府による確認は29日に発覚した香港籍の貨物船に続き2例目。

聯合ニュースは31日、北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いのあるパナマ船籍の運搬船を、韓国西部の港で当局が調べていると伝えた。事実なら、韓国政府による北朝鮮船への移し替え確認は、南部の麗水港で検査した香港船籍の貨物船「ライトハウス・ウィンモア」に次ぎ2例目となる。

聯合によると、韓国当局は「北朝鮮との関連が疑われる船舶」としてパナマ船籍の「KOTI」号を調べている。船員の大部分は中国人やミャンマー人。出港を許可せず、調査には関税庁や情報機関の国家情報院が当たっているという。

国連安全保障理事会は9月、海上で北朝鮮の船に積み荷を移すことを禁止する制裁決議を採択した。しかし、既に韓国が確認した香港船籍の貨物船のほか、ロシア船籍の複数のタンカーも過去数カ月間に北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えたとの報道もある。(共同)

【ソウル聯合ニュース】北朝鮮船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いで、パナマ船籍の石油タンカー「KOTI」号(5100トン)が韓国西部の平沢・唐津港で関税庁など関連機関の検査を受けていることが31日分かった。平沢地方海洋水産庁が明らかにした。

乗船していたのは中国人とミャンマー人が大部分で、関税庁と情報機関・国家情報院が合同で調べを進めているもようだ。

韓国政府は29日にも、香港籍の船「ライトハウス・ウィンモア」号が10月に公海上で石油精製品600トンを北朝鮮船舶に移し替えたことを確認したと発表した。11月に韓国南部・麗水に寄港した同船は検査を受け、抑留されている。

国連安全保障理事会は9月、海上で北朝鮮船舶へ積み荷を移すことを禁止する制裁決議を採択している。パナマ籍の船の嫌疑が確認されれば、この制裁決議への違反で韓国当局が船舶を摘発するのは2度目となる。

座礁船、1年半放置 沖縄、所有者と連絡取れず 09/02/14 (産経新聞)

沖縄県・伊良部島(宮古島市)近海の浅瀬で、昨年1月に座礁したモンゴル船籍の小型タンカーTJ88(99トン)が船体を傾けたまま放置されている。ダイビングスポットも近いコバルトブルーの海の景観を害しており、台風などの影響で動きだせば思わぬ被害も出かねない。しかし「所有者と連絡が取れない」(海上保安庁)状態で、撤去の見通しは立っていない。TJ88はシンガポールへ航行中の昨年1月14日、強風にあおられて浅瀬に乗り上げ、ミャンマー人乗員7人のうち1人が死亡、1人が行方不明となった。海保がシンガポール在住の所有者に船体の撤去を指導したが、その後連絡が取れなくなった。海保は「継続的に電話しているが、担当者に取り次いでくれない」と漏らす。宮古島海上保安署によると、TJ88は伊良部島の北方の岩礁にはまったまま波をかぶっており、巡視船が定期的に監視。油の流出はないが、事故からしばらくたっても「船が乗り上げている」という観光客からの118番が数回あった。

今月4日、全羅南道麗水市(チョンラナムド・ヨスシ)の巨文島(コムンド)から南東34カイリ(約63キロ)の公海上。北朝鮮船員16人が乗ったモンゴル国籍の4300トン級貨物船「グランドフォーチュン1号」が沈没した。

韓国の海洋警察は救助活動を行って5人を救助したが、2人は死亡し、追加捜索を行って1人の遺体を引き揚げた。救助された3人と遺体3体は板門店(パンムンジョム)を経由して北朝鮮に送った。海洋警察や麗水警察署などによれば、沈没した船は北朝鮮の清津(チョンジン)港から出発して中国揚州市近隣の江都港へ向けて航海中だった。重油50トンや鉄鉱石などが載っていた。韓国政府は14日、最後の遺体1体を北朝鮮に引き渡した。

グランドフォーチュン1号は海がない内陸国、モンゴル国籍の船だった。船主は香港にある会社だった。海洋水産部などは船主が「便宜置籍」の一環としてモンゴルに船を登録して賃金が安い北朝鮮船員を雇用し、貨物事業を展開していたと推測した。

便宜置籍は、自国船員の義務雇用比率を避けて税金節約のために他国に船を登録することをいう。それ自体は違法ではない。パナマやリベリア国籍の船が多いのは便宜置籍が多い国だからだ。

モンゴルは内陸国だが2003年から船舶登録局を開設して他国の船の登録を受けている。船舶登録を受けて税金を集めて海運産業を育成するためだ。ウィキリークスが2007年に公開した米国大使館の資料によれば、モンゴルには283隻が登録されている。船の主人の国籍はシンガポール(91隻)、パナマ(22隻)、マレーシア(22隻)、香港(12隻)などだった。船主が国籍不明な船も39隻あった。

北朝鮮が香港会社を代理船主として前面に出し、モンゴルに船を登録した可能性を見せている部分だ。外交部関係者は「今回のグランドフォーチュン号は、韓国領海ではない公海上で発見されたので対北朝鮮制裁決議にともなう船舶の捜索や調査を行えなかった」として「すぐに目についた重油や鉄鉱石のほかに、どんな物があったのかは確認できなかった」と話した。

先月出てきた国連安保理の対北朝鮮制裁の専門家パネル報告書によれば、国籍は北朝鮮ではないが実際は北朝鮮の船と疑われるものが最低8隻以上だった。このうちスンリ2号、グンザリ号、クァンミョン号の3隻は、今回発見されたグランドフォーチュン1号のようにモンゴルに登録されている。他国の国籍を持っており、船主は香港人である船も1隻あった。

国連対北朝鮮制裁の専門家パネルは報告書を通じて「安保理の対北朝鮮制裁決議2094号(2013年)が発効された後、北朝鮮は船舶を再登録したり国籍を変更したりして制裁を避けようとする可能性が高い」と指摘した。実際に北朝鮮は昨年だけで4隻の船をカンボジア・トーゴなどに国籍を変更した。

このような前例もある。2011年5月、北朝鮮の南浦港(ナムポハン)からミサイル武器などと推定される部品を載せてミャンマーへ向かった「ライト」号は、米国海軍の追撃を受けると公海上にとどまって回航した。ライト号は2006年まで「ブヨン1号」という名前を使う北朝鮮国籍の船舶だったが、北朝鮮核実験後に対北制裁が激しくなると名前を「ライト」に変えて国籍も中米のベリーズに変更して運行した。「ライト」号は米国の取り締まりがあってから2カ月後、アフリカのシエラレオネで国籍を変えて船の名前も「ビクトリー3号」に変更した。国連の対北朝鮮制裁の専門家パネルは、国籍を「洗浄」した北朝鮮の船が19隻以上に上ると推定している。

SURVEYORS contracted by the government maritime agency administering Panama's flag registry are not conducting thorough annual flag-state inspections and have not been paid for six months, some of those working within the international network have alleged. The Panama Maritime Authority (AMP) is pocketing more money but there is a "dangerous drop" in inspection quality, which has worrying implications for the AMP and the IMO, which regulates it, say the surveyors. Sources familiar with the issue confirmed the back payment problems, but were unable to comment about the quality of vessel safety inspections. The AMP collects about $1,000 from each ship registered as part of an annual inspection fee, from which surveyors receive $300. AMP figures show that more than $21.2M has been collected since 1999 from inspection fees. Panama flag state inspectors first raised technical and safety concerns in 2000 and 2001 after surveyors' payments fell more than 18 months behind. The AMP said as recently as early 2002 that all surveyor payments were up to date, following an audit to confirm outstanding money owed. The flag state network of surveyors stood at 143 in 2001, after the AMP sacked as many as 200 surveyors.

13 June 2003

山口・下関港に27日に入港する予定のカンボジア船籍の貨物船が、北朝鮮へ向け中古自動車などを運ぶことがわかった。去年10月の経済制裁以降、下関港から北朝鮮へ輸出品を載せた船が向かうのは初めて。

下関港に入港を予定しているのは、カンボジア船籍の貨物船「KENYO」(900トン)。下関市港湾事務所によると、韓国・釜山港から27日に下関港に入港し、中古自動車などを積み込んで、今月30日に北朝鮮・興南港に向かうという。下関港には、北朝鮮に運ばれるとみられる中古のバスやトラックなど約30台がすでに置かれている。

下関港は、北朝鮮の貨物船が数多く入港していたが、政府は北朝鮮の核実験を受け、去年10月、北朝鮮船籍の貨物船の入港を禁止するなどの制裁措置に踏み切った。この制裁以降、下関港から輸出品を載せた船が北朝鮮に向かうのは、今回が初めて。

また、政府は、牛肉や香水、乗用車など24品目の「ぜいたく品」の北朝鮮への輸出を禁止している。今回、下関港から北朝鮮へ向かう貨物船は船籍、船主ともカンボジアで、中古の自動車などもぜいたく品に該当せず、問題はないという。

今月16日には、鳥取・境港でカンボジア船籍の貨物船が中古の自動車や自転車を積んで北朝鮮に向け出港した。今後、ほかの国の船を使った北朝鮮への輸出が増えることも考えられ、経済制裁の実効性が問われる事態も予想される。

海運雑誌「Fairplay」に興味深い記事が書かれている。タイトルが 「Erika trial set for 2005」と言う記事である。

海運雑誌「Fairplay」に興味深い記事が書かれている。タイトルが 「Erika trial set for 2005」と言う記事である。

この記事の中に 「Also among the indicted is Malta Maritime Authority, which has asked the Paris Court of Appeal to cancel charges that blame it for accepting a sub-standard vessel in its registry. 」と書かれている。 サブ・スタンダード船 登録したマルタ国にも責任があるとして告訴している点である。マルタ籍船舶や登録制度についてはよく知らないが、 サブ・スタンダード船 であるか登録する前に適切なチェックも行わず登録する 旗国は存在する。アジアでは、最近目立つ 旗国船は モンゴル籍船や カンボジア籍船 である。これらの船籍は、日本から売却された船舶を輸出する時に よく使われている(いた)。 売却され日本から出港した例はいくつかある。

知られている例は、売船された後、輸出許可のために パナマ籍に登録され、神戸から出港した日に沈没したマリナ アイリス インドネシア国籍の乗組員6人のうち、4名が死亡、2人が行方不明となった。 後に、シンガポールで船主と保険会社が争い、裁判となり、船は遠洋航海に不適切な状態で出港し、 船員は国際航海に必要とされる免状の資格を持っていない事が判明した。

売船された後、輸出許可のために フィリピン籍に登録され、尾道から出港したマリアも沈没した。 フィリピン国籍の乗組員8人のうち、7人が行方不明、1人が救出された。 船がどのような状態で出港したかは PSC(外国船舶監督官) と保安庁のみ知る。

現在の状況についてはよく知らないが、税関や国土交通省はよく知って いると思われる。全ての旗国が適切なチェックを行っていれば、 サブ・スタンダード船(sub-standard vessel) の逃げ道はふさがれるはずである。国土交通省(日本)もこのような状況を把握した上で 各国の検査制度を監査する提案をしたのであろう。 まあ、それにしては旗国の検査官に問題があるように思えても、旗国の検査官の判断を尊重する 傾向が日本のPSCにあるのはおかしい点であるが、これから改善されると推測する。

サブスタンダード船(sub-standard vessel) がこれまで以上に厳しく検査される と思われるので様子を見守りたい。

水産大学校 練習船 耕洋丸が売船され、セント・キッツ籍の船名「NORTHERN QUEEN」 となった船がどのような使われ方をされているのか調査すれば、おもしろいことがわかるかもしれない。個人的に違法な操業に関わっている 可能性は高いと思う。

第65次FOCキャンペーン、香港籍など未組織FOC船に照準

チェック(監査)の甘い旗国(国)は悪質な船主やオペレーターに利用される。 PSCO(外国船舶監督官) の中にはこの事実に気付いている人もいるだろう。 中には悪質な船主やオペレーターと共存、共栄の関係の旗国(国)もあるだろう。 このような環境を改善できるのは PSCO(外国船舶監督官) だけであろう。 なぜなら、旗国(国)が改革すれば、規制・監督の甘い旗国(国)へ船舶の 登録を変えるだけだからである。

PSCO(外国船舶監督官) が問題解決に有効である。しかし、 PSCO(外国船舶監督官) の能力や経験が低い、取締りに対する姿勢に問題がある場合、検査を行っているにも 関わらず、結果に反映されない問題もある。現状を知りたい人は下記のHPを参考にしてほしい。

「大阪市の業者も所有船の船籍について、日本船籍を残したままパナマ船籍を取得し、 船尾に正しい船籍を標示していなかった疑いが持たれている。04年5月末から約2年間、 北朝鮮の砂利運搬事業をしていたという。」

これは、2年間、旗国による検査を受けていないことを意味している、または、旗国の検査を 受けているのであれば、旗国の検査に問題があることを示している。

PSC(外国船舶監督官) の検査レベルが検査官の能力や経験により、大きな差がある。 これは、旗国の管理やチェック体制に問題があっても、日本に入港してくる船舶は チェックされ、問題を指摘される可能性を低くしている。

疑問な点もある。「パナマの仮船籍を取得した際に、同法の規定で抹消されなければならない日本船籍が 残ったままになっていたこと」と書かれているが、全ての書類を提出しなければ、本国籍証書は 発行されない。仮国籍が発行されていても、日本国籍の内航船の装備では国際条約の要求を満足しない。 「昨年8月22日、この船が福岡市の博多港に寄港した際、巡回中の第7管区海上保安本部が検査を実施。」 した時に、第7管区海上保安本部が PSC(外国船舶監督官) を呼べば、出港停止は避けられない。外国船舶監督官を呼んでいたのであれば、出港停止になっていた はずである。出港停止になっていなければ、重大な問題だ。

「日本船籍を残したままパナマ船籍を取得し、船尾に正しい船籍を標示していなかった疑いが持たれている。」 これについても、同様なことは広島県の尾道でも起こっていた。 尾道の保安職員や税関は、対応していなかった。

結局、パナマ籍船のチェック機能の甘さと日本のチェック機能の甘さ、そして対応の遅さが まねいた事件だ。

北朝鮮の海砂運搬事業に参入するためにパナマ籍などに船籍を偽装した疑いが強まったとして、海上保安庁が、長崎県佐世保市と大阪市の海運業者や所有船などを、船舶法違反(船名等の標示違反)などの疑いで捜索していたことが16日、分かった。北朝鮮と韓国の業者の間で、この事業には日本船籍は使わないと取り決めていたため、偽装したという。同庁は来週にも2業者を書類送検する方針だが、ほかにも同じ不正をして、この事業に船を派遣した業者が数社あるとみて調べている。

同庁や関係者によると、この事業は北朝鮮の商社と韓国の建設業者の間で04年3月に始まった。北朝鮮の海州沖で採取した海砂を、運搬船に積み込んで韓国や中国に搬送するもので、北朝鮮の外貨獲得手段の一つという。同庁などは、北朝鮮はこの事業で06年に約600万ドル(約7億円)の外貨を稼いでいたとみており、これに日本の海運業者が関与した形だ。

調べでは、佐世保市の業者は04年10月初め、自社の所有船(1599トン)が日本籍なのに、韓国・ソウルのパナマ大使館で不正にパナマの仮船籍を取得するなどした疑いが持たれている。

同年11月6日~06年4月14日、北朝鮮・海州~韓国・仁川間を約140往復、韓国・仁川~中国・威海を7往復、韓国の建設業者の下請け船としてピストン運航していたとみられている。

昨年8月22日、この船が福岡市の博多港に寄港した際、巡回中の第7管区海上保安本部が検査を実施。パナマの仮船籍を取得した際に、同法の規定で抹消されなければならない日本船籍が残ったままになっていたことなどから、昨年10月に同社や関連会社など3カ所を家宅捜索した。

この際に押収した日誌や通帳などから、北朝鮮の海砂事業で約1億2500万円の収益を得ていたことが判明。他の業者に「砂ビジネスはもうかる」などと参加を勧めるメモも見つかった。

一方、大阪市の業者も所有船の船籍について、日本船籍を残したままパナマ船籍を取得し、船尾に正しい船籍を標示していなかった疑いが持たれている。04年5月末から約2年間、北朝鮮の砂利運搬事業をしていたという。

フィリピン籍タンカーが沈没し、 かなりの被害を出しているようだ。詳細はこちらを参考に。 ★フィリピン籍タンカー船「SOLAR1」

With the condemnation that Panama has been getting from the maritime industry both in the local front and to some extent, in the international arena, due to yet another questionable ‘mandatory training initiative’ from the Panamanian Maritime Directorate, the ongoing effort of the Maritime Industry Authority (MARINA) to promote and expand the Philippine ship registry now appears to be a ray of light at the end of the tunnel.

MARINA Administrator Vicente Suazo Jr. disclosed to Tinig ng Marino that efforts are continuously being made to incorporate the promotion and further development of the Philippine ship registry into the National Development Agenda to be able to give foreign shipowners a viable and sound alternative to flag of convenience (FOC) registries.

“We want the Philippine ship registry to become the new FOC for foreign shipowners, not a flag of convenience but a Flag of Choice,” cites Suazo.

“It is our vision for the Philippines to be a key player in the global maritime industry with a fleet of competitive vessels serving the domestic, regional and international trades, with an abundant pool of seafarers, compliant with global and national standards for quality, safety, security and maritime environmental conservation in support of our national development and economic recovery,” explains the MARINA Administrator.

“The promotion and expansion of the Philippine ship registry through the establishment of ship management companies in the country not only give flesh and realization to such vision but creates a conducive environment to investors as it improves the industry’s competitiveness and reduces the cost of doing business in the Philippines,” Suazo further pointed out.

“I’d like to point out that we are not just working to attract just about any type of shipowners. The Philippine ship registry will not be another run-of-the-mill flag of convenience, that’s for sure. While we have initiated talks and in the process, gained commitments from some shipowners to consider the Philippine ship registry, we also clearly expressed to them that the Philippine registry’s major concern is safety and that it is strictly adhering to existing IMO rules, regulations and conventions,” stresses Suazo.

Suazo also cited that a strong Philippine ship registry will maximize the economic opportunities that the government can derive from the maritime sector.

“This is a perfect opportunity for the country’s maritime industry to finally come out of its shell. If small countries like Panama, Bahamas, Malta and others can make a strong economic living out of global maritime trade, why can’t the Philippines, a legitimate maritime nation more than them, can live up to it and make the most of its potentials?” raises Suazo.

The MARINA administrator specified the country’s three major potentials in becoming a formidable Flag of Choice for shipowners.

“We are the top supplier of seaborne manpower in the global merchant fleet. We have the best available ship managers in the Philippines. If and when foreign shipowners decide to put up ship management offices here in the country, they need not hire the services of foreign personnel and bring in high-maintenance expats because we have plenty of able and very competent ship managers all over the local maritime industry. And lastly, we have a ship registry that is on the verge of expanding and becoming a formidable one in the next few years,” explains Suazo.

Compared to 400 vessels back in 1989, the Philippine ship registry now has only 170 vessels. “It used to be 168 vessels but over the last couple of months, two vessels were added to the roster after I was able to convince a couple of shipowners to consider the advantages of having their ships fly the Philippine flag. In fact, we are looking at two more additions by February 2007 from a Dubai shipowner and another one from Cyprus,” the MARINA administrator revealed.

While MARINA’s efforts to promote the Philippine ship registry are reaping dividends at a gradual pace as of yet, Suazo is confident that a groundswell impact is up and coming in the near future. In fact, he is so confident that MARINA is moving towards the right direction in the promotion of the local ship registry that he even divulged that they are targeting 1,000 vessels to fly the Philippine flag in the next couple of years.

Suazo also disclosed that MARINA has drafted and proposed an Executive Order, coursed through Transportation and Communications Secretary Leandro Mendoza, for consideration by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, whose approval will pave the way for the further strengthening of the Philippine registry by liberalizing the implementation of the Bareboat Charter Rules that is still in effect until 2009.

“While the Philippines has the potential to be a very successful flag registry, what has held it back over the years from realizing its full potentials are ambiguity of laws and lack of initiatives to spur further development and increase its existing fleet,” observes the MARINA Administrator.

“What is required is the government’s support in order for Philippine-registered ships to compete in the global transportation business with foreign ships and the importance of containing costs and minimizing competitive pressures for ship management companies doing business in the country,” identified Suazo.

“The EO will ease governmental requirements on shipowners whose vessels are flying the Philippine flag. It will liberalize the Bareboat Charter Rules by taking away its disincentive provisions, which have really become a turn off for many shipowners,” remarks Suazo.

The MARINA Administrator particularly cited the levying of 4.5% withholding tax on Philippine-flag vessels carrying Philippine cargos, when in fact the government cannot impose the same charges on foreign-flagged vessels carrying Philippine cargos.

“That is the reason why NFA rice shipments, among other commodities for the Philippine market, are being transported by Vietnam-flag vessels, rather than Philippine-flag ships, as the rightful scenario should be. It has become a financial burden on the part of Philippine-flag vessels to carry Philippine cargos. They certainly can’t compete with foreign-flagged vessels,” cites Suazo.

“Allowing this situation to continue is tantamount to driving away shipowners to register with other flags. Through the EO, we are now addressing such major disincentive, among a few other loopholes in the existing Bareboat Charter Rules,” he added.

“In place of withholding taxes on Philippine-flag vessels, the Philippine ship registry will charge vessels on the basis of tonnage dues. Although tonnage dues will not be as much for each vessel, when compared to withholding taxes, this will be eventually offset by quantity or the expected significant increase in the number of vessels that will fly the Philippine flag,” Suazo elaborated.

結構良いことが書かれている。しかし、 カンボジア籍や モンゴル籍 の紹介でも良い事ばかり書かれていた。現実は違う。。詐欺と似ている。書いていることと実際が大きな違いがあるから騙されるのである。

フィリピン籍タンカー船「SOLAR1」 についていろいろと書かれているが、記事の70~80%が事実とすれば、 フィリピン政府自体にも責任がある。船舶はフィリピンに登録されているのだから 管理や監督はフィリピン政府の責任である。全ての旗国がおなじような制度を採用している わけではないが、旗国によっては、船が登録される前、又は、登録された後、半年以内に 旗国による検査を要求している。また、多くの旗国が年次検査(Annual Inspection)を旗国の 検査として行っている。フィリピン籍の規則については全く知識がないが、フィリピン籍は どのようなシステムになっているのか。フィリピン籍貨物船が横浜へ武器を運ぶのに使われていた事実 もある。もし、旗国の年次検査(Annual Inspection)が検査が行われていれば、不正な改造、 検査のごまかし、積み過ぎ、船員の免状及びその他のライセンスのチェックなどの問題点が 指摘されると推測される。事故が起こってからの調査で発覚するようでは、問題のある 旗国と思われても仕方がない。比海事産業庁に派遣されている国際協力機構(JICA)の 日本人専門家もフィリピン籍タンカー船「SOLAR1」の件についていろいろと調べている ようなので、調査結果を公表してほしい。記事に書かれているようにFOCがFLAG OF CHICEなのか FLAG OF CONVENIENCEなのか、わかるかもしれない。

一般に 日本籍内航船 は国際条約を満足しない規則で建造されており、日本領海内(平水、沿海、非国際近海) でしか運航できない。国際近海(外国港への入港が可能)は国際条約を満たすように 建造されている。このため、日本籍内航船(国際近海として建造された船舶は除く)が外国籍になった時点で サブスタンダード船となる。 PSC(外国船舶監督官) がこの事実を理解し、予習をして元 日本籍内航船 の外国船を検査すれば、出港停止に値する不備を簡単に見つけることが出来る。 しかし、現実は一部の PSC(外国船舶監督官) 以外は見つけていない。

これは 日本のPSC(外国船舶監督官) を含むアジアのPSCが問題点を指摘していない(出来るだけの知識と能力がない)現状が存在するから成り立つのです。 国際船級協会連合(IACS)の 船級規則で遠洋区域(Ocean Going)の要求を満足する内航船などほとんどありません。

内航船として使われている「フェリーよなくに」に関して国境の離島における短国際航海(与那国−花蓮間60 海里)の貨客船あるいは貨物船の航行許可に関する要件緩和もしくは地域の実情をふまえた規制適用等

(財団法人都市経済研究所より)

からも推測できるが、内航船を改造することなしに国際航海に従事することは不可能だ。

しかし、船の国籍を選べば、

PSC(外国船舶監督官)

が問題を指摘しない現状では逃げ道があるのです。

検査会社が検査を見逃してやり、お金と引き換えに証書を発給するから多くの船が日本に入港出来るのです。

事実を知らないから、上記のような発想が出来るのでしょうね。

産地偽装問題

も同じですが、正直者がばかを見るのが現在の日本です。

外国人に対して強い対応が出来ない日本の公務員が生み出した矛盾です。

これを読んだ人達の中には割り切れない矛盾を感じる人がいるかもしれません。しかし、これが現実です。

サブ・スタンダード船のメリットそして取締る側の官庁の現実を考えるとサブ・スタンダード船 はなくならない。 第2回パリMOU・東京MOU合同閣僚級会議の結果について (サブスタンダード船の排除に向けた我が国の決意を表明)(国土交通省のHP) はリップサービスなのである。

下記の記事は2006年4月4日付けの記事である。2011年5月の現在でもカンボジア船籍船の多くはサブスタンダード船であり、多くの国々で出港停止命令を受けている。 外国船舶監督官(PSC)による検査で何が大きく変わったのか。大きな変化はない。 なぜ大きな変化は起きなかったのか。外国船舶監督官(PSC)による検査 が厳しくないからである。日本の公務員達による検査は甘い。

船籍国と船級協会 合田 浩之 (一般財団法人 山縣記念財団)