なぜ、サブスタンダード船 Why do Substandard ships exist?

UNDER-PERFORMING SHIPS (1年間に3回以上出港停止を受けた船舶) TOKYO MOUのHP

外国船舶油等防除対策費補助金がヘレナ2 (HELENAⅡ, 2,736トン,所有者:MOUNTAIN STAR INCORPORATED BAHAMA NASSAU, 運航者:SANTA LIMITED)の撤去に使われた。

外国船舶(油タンカーを除く)の座礁等による油流出事故において船主等が油防除を行わず、法律に基づく海上保安庁の要請により地方公共団体が油防除を実施した後、その費用を船主等から回収できなかったときに、事業費に対して1/2の補助を行う。

平成17年 船名:HELENAⅡ 交付対象:青森県と平成20年 船名:AAA UFULI 交付対象:佐伯市(大分県)に対して交付された。(国土交通省)

なぜ、サブ・スタンダード船が存在するのか。 はっきり言えば、ごまかしてお金儲けをしたい。 このような船主や船舶運航者が世界中に存在する。国際基準(規則を満足する)を満たすには、 お金が掛かる。PSC(外国船舶監督官)に 見つからないのなら、ごまかそう。取締が緩いので、何とかなるだろう。 PSC(外国船舶監督官)から出港停止などの処分を受けないと、これが当然となる。 儲けも増える。違反(非常識)が常識となる。

ごまかすのではなく、船の不適切な運用のため、まともな旗国では登録できない、又は、登録抹消になる可能性があるので、特定の旗国に登録する場合がある。

このような理由のため特定の旗国に登録される船はサブスタンダード船である可能性が高くなる。

北海道苫小牧市の食肉加工卸会社「ミートホープ」のミンチ偽装問題

、

農林水産省

及び

北海道庁

の関係を考えてもらえれば、素人の人達にも理解してもらえるだろう。不正を見つける機会は幾度となく

あった。しかし、農林水産省

と

北海道庁

の甘いチェックと立ち入り検査で問題を発見出来なかった(しなかった)。

構造計算書偽造

では、強度偽装を見逃していた「イーホームズ」に建築確認の依頼が集中した。

構造計算書偽造 民間の指定確認検査機関のずさんな検査

の問題として考えていただければ、理解できるであろう。

北海道苫小牧市の食肉加工卸会社「ミートホープ」のミンチ偽装問題

、

農林水産省

及び

北海道庁

の関係を考えてもらえれば、素人の人達にも理解してもらえるだろう。不正を見つける機会は幾度となく

あった。しかし、農林水産省

と

北海道庁

の甘いチェックと立ち入り検査で問題を発見出来なかった(しなかった)。

構造計算書偽造

では、強度偽装を見逃していた「イーホームズ」に建築確認の依頼が集中した。

構造計算書偽造 民間の指定確認検査機関のずさんな検査

の問題として考えていただければ、理解できるであろう。

船の場合、どうするのか? 監督(監査)が甘い国(旗国)を選ぶ。 検査をごまかす検査会社を選ぶ。例としては カンボジア籍船やモンゴル籍船が よく知られている。モンゴル政府も対応を考えているようだ。しかし、適切な対応を取れば他の国へ顧客が変わるだけだろう。 選ばれる理由が適切な管理監督を行っていない国。PSC(外国船舶監督官)が厳しい検査を 行わない限り、ニーズと供給はいつも存在するのでサブ・スタンダード船はなくならない。 社会が成熟しようが、先進国になろうが、警察が存在しようが殺人事件が無くならないのと同じ。サブ・スタンダード船 は減少することはあるだろうが、なくなることはないだろう。

RESOLUTION A.789(19) SPECIFICATIONS ON THE SURVEY AND CERTIFICATION FUNCTIONS OF RECOGNIZED ORGANIZATIONS ACTING ON BEHALF OF THE ADMINISTRATION (IMO)には 旗国の代わりに国際条約で要求される証書を発給する検査会社(RO)の最低限の要求が記載されている。 しかし、問題のある検査会社は守っていない。問題のある検査会社を取り締まるシステムもない。 PSC(外国船舶監督官)がサブ・スタンダード船を 取り締まる事によって不正な検査を間接的に止める事しか出来ない。しかし現状はPSCの検査はそれほど厳しくない。 このような現状で外国のPSC(外国船舶監督官)に研修を行うのは効率的なのか疑問だ。 結局はある部分を一般財団法人日本造船技術センター(SRC)に研修委託で丸投げしている。開けない場合は、ここをクリック 日本造船技術センター(SRC)/A>は検査業務を行っていないのに研修を行う。主要業務は船舶の設計および建造がメイン。 形だけのパフォーマンス、日本の国際貢献のアピールであるのなら結果を求めていないのでそれでも良いのかもしれない。しかし、 税金が非効率に使われるのは納得がいかない。 詳細についてはPSC(外国船舶監督官)のサイトを参考にしてほしい。下記のような不備を指摘できないのだから、日本の PSC(外国船舶監督官)もたいしたレベルでないことがわかる。

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

サンプル 4 2003年の3月に撮影。

PSCによる検査が2003年2月に行われた。不備としての指摘なし。

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

|

チェーンパイプが腐食し、多数の穴がある。2ヶ月でこのように急速に腐食する事はない。 また、このチェーンパイプを見ただけで腐食が疑える。 |

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

||

ISM(国際安全管理規則)コードによる船舶安全管理認定書(SMC)を取得している船舶D

こんなタンカーが日本で油汚染を起こせば、何十億から何百億の被害は出るであろう。規則は厳しくなるのに、こんな抜け道が存在する。 個人的な経験では、検査会社(Overseas Marine Certification Services)にこのような大型タンカーを検査出来る能力や検査官は存在しないと思う。 タンカーの船齢は25年。手入れが悪ければ何があっても不思議ではない。

しかし、でたらめな検査を行ったとの理由で検査が出来なくなった検査会社は少ない。例え、検査できなくなってもまともな検査を行わないぐらいの会社で あるので何でもやる。名前を変えて、再出発するだけ。この事を知っているPSC(外国船舶監督官)は何人いるのだろうか?

税金で外国船が引き起こす海難の尻拭いだけはやめてほしい。問題がある外国船が入港出来ないようにPSC(外国船舶監督官) はしっかりと検査するべき。甘い検査をしているから、三流の検査会社が調子に乗って何でもやるのである。

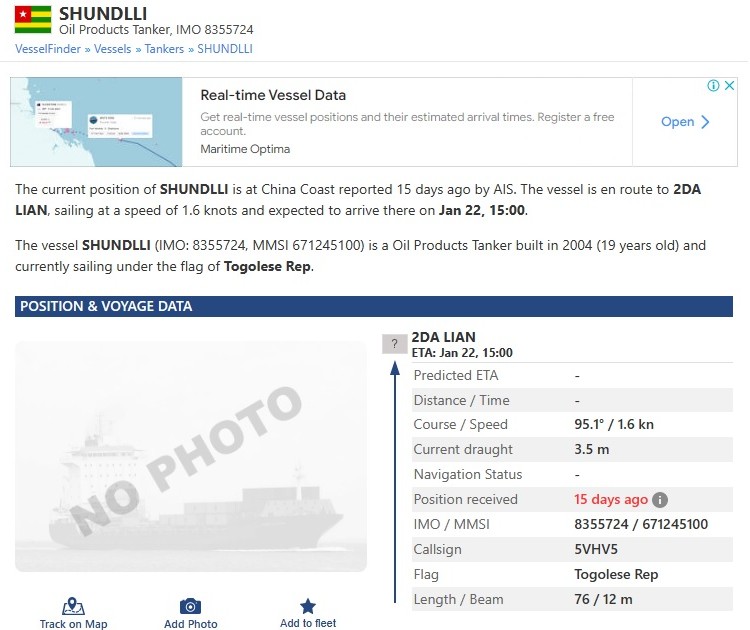

3千トン級バルク船(DEYI号):IMO8360676は韓国と中国の航海ではAIS:船舶自動識別装置の電源を入れているが、ロシアへの航海では記録が残らなように電源をオフにしているようだ。日本に来たことがあるのかは不明。ただ、 トーゴ籍船に問題がある船が含まれていると考えて間違いなないと思える。

トーゴ籍船に問題がある船が含まれていると考えて間違いなないと思える。

韓国当局が対北朝鮮制裁違反への関与が疑われる無国籍船を拿捕したことが分かった=3日、釜山(聯合ニュース)

政府当局が拿捕して抑留中の3千トン級バルク船(DEYI号)が、2月には北朝鮮で貨物を積んだ後、中国に運搬したことが分かった。韓国政府は、北朝鮮の南浦(ナムポ)港で無煙炭を積んだ後、ロシアに向かっていたこの船舶を米国の要請を受けて先月末に拿捕した。これに先立ち、この船舶が中国にも北朝鮮の石炭などを輸出したことが今回確認された。国連安全保障理事会の対北朝鮮制裁決議は、北朝鮮の石炭輸出などを厳しく制限している。

4日の東亜(トンア)日報の取材を総合すると、韓米当局は、DEYI号が政府に摘発される約1ヵ月前の2月に船舶自動識別装置(AIS)をオフにして北朝鮮付近で貨物を積み込み、これを中国で荷揚げしたと見ている。政府消息筋は、「この船舶が対北朝鮮制裁を違反したと韓米が判断した主な状況」と明らかにした。この船舶は、南浦港など北朝鮮の港に入港したり、近隣の海上で積み替える方式で石炭などを運んだとみられる。最近、北朝鮮と中国の近海では、違法な積み替え活動と疑われる船舶が多数出現したという。

DEYI号が今年1月に中国山東省の威海港を出港し、釜山(プサン)港に入港したことも確認された。DEYI号は当時、韓国港湾当局に目的地をウラジオストクと届けたが、釜山港を出港した後、AISをオフにして姿をくらました。これを含め、この船舶がAISをオンにして公開運航記録を残したのはこの1年間で2件にすぎない。そのため、韓米当局はDEYI号がAISをオフにして長期間、対北朝鮮制裁違反活動を続けてきたと推定している。

DEYI号は香港所在の会社が所有する船舶と把握された。「アジア太平洋地域港湾局統制委員会安全検査資料」などによると、この船舶は「香港ウィリム海運有限公司」が所有主と表記されている。ただし、2022年2月に設立された同社は、香港市内のショッピングセンターの建物に住所を登記している。業種や電話番号などは一切公表していない。

DEYI号は06年2月から22年8月まで約16年、中国国旗を掲げて航海していたが、昨年5月からトーゴ国旗に変えて運航していたことが分かった。現在はトーゴ国旗の期限も切れて無国籍だ。

船社が香港にあるにもかかわらず、このように国旗を別の場所に変えたのは、「便宜置籍(船舶を自国ではなく第3国に登録する)」制度を活用するためとみられる。船舶に対する管轄・管理の責任は、船舶が掲げている旗、つまり旗国にあるという原則がある。そのため、旗を変えれば、公海上で問題が発生しても、この原則のために国際社会の積極的な制裁が難しくなる可能性がある。一部ではこれをめぐって、「国連安保理の対北朝鮮制裁を回避することが狙い」という批判もある。

北朝鮮が違法な石炭輸出のために香港に幽霊会社を設立し、船舶を運航した可能性も否定できない。18年に国連の対北朝鮮制裁対象に指定された北朝鮮の船舶「長安号」も、香港に設立された「長安海運技術有限公司」の所有だった。

申圭鎭

South Korea’s Foreign Ministry has confirmed media reports that it had detained a cargo ship that was underway near the port of Yeosu, transiting the waters between South Korea and Japan.

The Ministry said that the government was conducting an investigation based on cooperation with the US into allegations of sanctions violations by a general cargo ship named De Yi (IMO 8360676).

The vessel was asserted to have refused to stop when so ordered by the South Korean Coast Guard. The vessel was then redirected to Busan anchorage, where it arrived on March 30th. However, there are reports that the crew continued to refuse to cooperate, refusing so far to open the ship’s cargo hatches for inspection.

South Korea recently has taken an increased number of unilateral steps against North Korea. These have included sanctioning ships involved in the weapons trade with Russia and reportedly increasing monitoring of North Korea for sanctions violations.

Reports are calling the vessel stateless with international databases also listing the flag and ownership as unknown. Built in 2006, the vessel’s last known owner and operator was registered in Hong Kong. Since being built, the ship was registered in China, but it appears to have been sold in 2022. What looks to be a prime example of a “shadow fleet” vessel was renamed and in 2023 was registered as Togo-flagged, although that might no longer be operative.

South Korea said that the ship was believed to have been in North Korea’s Namo Port before proceeding to Shandong, China. At the time it was detained it was reporting Vladivostok, Russia as its destination. The report said there are 13 crewmembers, including a Chinese captain and Chinese and Indonesian crewmembers aboard.

Actions such as this against merchant ships that are underway are very rare. Such detentions as do take place tend to be when the vessel is in a port.

2006-built, 2,999 gt De Yi is reported as having a Hong Kong-addressed owner and manager. Marine Traffic has it as Togo-flagged. As of April 4th it was Stopped at Busan Anchorage.

3日、釜山甘川(プサン·カムチョン)港近くの墓薄地に北朝鮮制裁違反行為に関与した疑いが持たれている船舶(3000トン級·乗組員13人)が停泊している。 聯合ニュース

韓国当局が対北朝鮮制裁違反への関与が疑われる無国籍船を拿捕したことが分かった=3日、釜山(聯合ニュース)

「北朝鮮の石油取引に関するFTの調査で暴露された中国人ブローカーが逮捕された 」2023年1月31日ファイナンシャルタイムズ(Financial Times) の記事がある。メットオーシャン(Met Ocean)が運航していた中国船シュンドリ号 (Shundlli)):(Chinese ship called the Shundlli, which was operated by Met Ocean.)はトーゴ籍船だ。サブスタンダード船が犯罪や違法行為に使われるのは、船を登録する旗国の管理監督問題と検査会社の問題が相互にリンクして、犯罪や違法行為に使われやすい環境が出来上がっている。そしてPSCの検査が甘い国やエリア、そしてサブスタンダード船を知りながら見ないふりしたり、利用したり、接岸させる施設や関係者の間接的な対応で活動範囲が拡大できる。

Christian Davies and Song Jung-a in Seoul and Polina Ivanova in Berlin

A Chinese oil broker whose activities were exposed by a Financial Times investigation has been arrested in South Korea on suspicion of organising illegal transfers of diesel to North Korea.

The broker is suspected of arranging more than 35 transfers amounting to 18,000 tonnes of diesel, in deals valued by the South Korean coastguard at Won18bn ($14.6mn).

Investigators from the South Korean coastguard allege that the agent arranged for a Russian oil tanker operated by a South Korean oil company to conduct ship-to-ship fuel transfers with a Chinese vessel in the South China Sea. The Chinese ship then conducted ship-to-ship transfers with North Korean vessels, a violation of UN sanctions.

Last month, a joint investigation by the FT and the Royal United Services Institute think-tank tracked a separate delivery of marine oil last year from South Korea’s south-east coast into North Korea’s exclusive economic zone.

The investigation revealed that an unnamed Chinese shipping agent had brokered a deal between a South Korean company called Eastern Pec and a Shanghai-based company called Met Ocean Co to conduct a fuel transfer in the South China Sea.

The marine oil was transferred from South Korea to a meeting point by Eastern Pec using a Russian oil tanker called the Mercury, which it had chartered from a company based in Vladivostok. The cargo was then transferred to a Chinese ship called the Shundlli, which was operated by Met Ocean.

In a “letter of guarantee” seen by the FT, Met Ocean promised Eastern Pec not to deliver the shipment to North Korea. But satellite imagery and tracking data show the Shundlli going on to conduct an apparent transfer with a second ship in the North Korean EEZ.

The shipping agent, who is a naturalised South Korean national, was arrested on Saturday. On Tuesday, the coastguard confirmed to the FT that the agent was the same person who is alleged to have brokered the deal between Eastern Pec and Met Ocean. The coastguard said it took action amid fears the agent could become a flight risk after his activities were revealed.

The broker was detained on charges relating to shipments conducted between October 2021 and January 2022, which do not involve the Mercury, the Shundlli or Eastern Pec, the coastguard said. Investigations into the operation exposed by the FT were continuing, it added.

“The FT report helped us broaden our investigation, enabling us to ask the broker about other deals that he was involved in,” said a Korean coastguard official. “We are also investigating his other activities involving the Mercury and Eastern Pec.”

Eastern Pec has said that the operation revealed by the FT was the first time it had worked with the broker.

The UN Security Council imposed a cap on permitted oil transfers to North Korea in 2017 after Pyongyang’s sixth and most recent nuclear test. The ceiling of 500,000 barrels a year is far below the energy needs of the North Korean economy.

All such oil transfers must be reported to a UN sanctions committee, but in practice, only a fraction are. An unreported transfer constitutes a violation of the sanctions.

Go Myong-hyun, a sanctions expert at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in Seoul, said that the transfers helped prop up North Korea’s shattered economy, as well as Pyongyang’s capacity to train and field its armed forces and sustain its weapons development programmes.

“No matter how large or small, what this shows is that the South Korean authorities need to identify these operations and crack down on them hard,” he said.

Source: Financial Times

Elisabeth Braw

By Elisabeth Braw, a columnist at Foreign Policy and a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. FP subscribers can now receive alerts when new stories written by this author are published

The world’s top three ship-owning countries are China, Greece, and Japan. But the top three countries under which ships sail include none of these—nor fourth-ranked United States or fifth-ranked Germany. The flag league is instead led by Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands. They are flag-of-convenience states, economically weak countries that allow vessels to register in their ship registry for a much lower fee than developed countries. The lower fee comes with less service—and less scrutiny—than traditional maritime states offer. Although the former has made flag-of-convenience states popular with countless vessels over the past decades, the latter is now making them extremely attractive to vessels seeking to get around Western sanctions against Russia. Such vessels have begun switching to flag-of-convenience states—or even taken to sailing under their flag without telling them.

And these overburdened maritime nations do little to remove the squatters. Rickety tankers that should be headed for the junkyard are instead roaming the world’s oceans, bringing oil from Russia and its fellow sanctioned nations, Venezuela and Iran, to China and other customers. And it’ll take a major crisis to force the problem to the surface.

“Shipping companies that are trying to get around sanctions are targeting really small registries that are privately managed,” Lloyd’s List Intelligence maritime analyst Michelle Wiese Bockmann told Foreign Policy. “Then they either falsely claim that their ships are flagged there because the country will do nothing about it, or they legitimately flag the vessels there and get the country to issue false company IMO numbers,” referring to the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Every shipping company has an identification number with the IMO. But if a shipping company or vessel doesn’t want to be recognized, then they can trick a flag state’s registry into using fake IMO numbers—and since flag-of-convenience states’shipping registries are often poorly resourced, privately managed, or both, officials rarely spend serious time investigating IMO numbers. And shipping companies operating under a false IMO number can be traced only with extreme difficulty.

Shifting registries to avoid sanctions has been going on for a decade or so, ever since Iran’s state-owned oil company discovered that it could get around restrictions on its oil by having its shipping companies register their vessels with twin registries maintained by Tanzania and Zanzibar. (Zanzibar is now part of Tanzania, but the registries date back to the days when it was an independent state.)

Parking the Iranian tankers in the Tanzania-Zanzibar registry wasn’t exactly legitimate, since ships are not supposed to change flags simply to get around sanctions, but as Bockmann points out, “It was done with the knowledge of the privately owned company that manages the Tanzania-Zanzibar registry.” In fact, by registering its vessels in Tanzania-Zanzibar, Iran managed to continue exporting oil. Although traditional maritime states, such as Britain and Greece, comply with sanctions on goods that travel by sea, flag-of-convenience states are often laissez-faire regarding both vessels and cargo. And the world doesn’t have a maritime authority that can track every single vessel, especially if it changes its flag registrati

by The Editorial Team

The Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) detained four ships in Johor waters, on January 9, for illegal activities, including anchoring without permission and transferring oil illegally.

According to Johor MMEA director Maritime First Admiral Nurul Hizam Zakaria, the vessels are suspected of illegally transferring oil at a position of 32 nautical miles east of Tanjung Sedili Besar in Kota Tinggi.

For the offence of illegal oil transfers, 7,000 metric tonnes of Marine Fuel Oil (MFO) worth RM24.5 million were seized for investigation.

The first case was conducted between 10.50am and 11.30am by the agency’s marine patrol boat team on two tankers registered in Penang and Panama.

The second case occurred at 11.40am where a merchant ship from Douglas, Australia was detained at a position of 11.9 nautical miles east of Tanjung Siang.

The last case involved a tanker registered in Zanzibar, Tanzania and was manned by five Indonesian crew members, aged between 26 and 60, when they were detained at 4.14pm.

The detention of the third and fourth vessels was due to anchoring without permission and all crew members, including the respective vessel’s captains, were taken to the MMEA’s Tanjung Sedili Maritime Zone for further investigation.

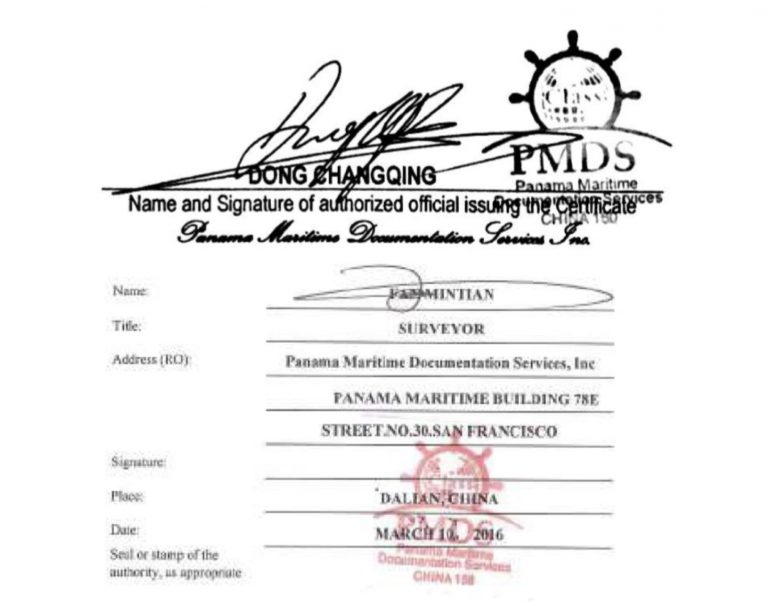

下記の記事はPanama Maritime Documentation Services (PMDS)と呼ばれるパナマから承認されている検査会社と検査官達の不正である。また、International Maritime Survey Association (IMSA)と呼ばれるモンゴルから承認されている検査会社と検査官の不正に関して書かれている。記事は北朝鮮、又は、北朝鮮に関与している船に関して証書を発給している事だけに言及している。

PSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員や国土交通省がどこまで情報を持っているのか知らないが、これらの検査会社は北朝鮮、又は、北朝鮮に関与している船に関して証書を発給している問題だけでなく、国際条約を満足していないサブスタンダード船に対して、船が運航できる証書を発給している問題がある。最近、ビックモーターの問題が注目を浴びているが、もし、国交省がPanama Maritime Documentation Services (PMDS)が検査したサブスタンダード船に対する検査程度の調査しかしなければ、甘い対応で終わりであろう。残念だが、個人的にはPSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員の検査は甘いと思う。また、検査する船や検査する項目が的外れだと思う。本当の意味での取り締まりであれば、問題があると思われる船に絞るべきだと思う。良い船を検査して、検査官の数が足りないから全ての船を検査できないとか言っているのであれば、本当にあんぽんたんか、やる気がないと思う。

PSC(ポート・ステート・コントロール;国土交通省職員の検査が甘いと、たくさんのサブスタンダード船が日本に入港するので、入港及び出港の過程で事故を起こす可能性はある。そして、放置される可能性はある。放置されると日本国民の税金で撤去される事となる。

Sabine Knapp, Philip Hans Franses, Bruce Whitby

Highlights

Kok Leong, executive editor

The United Nations and World Bank estimated that corruption can add up to 10 percent to the cost of doing business globally. It fundamentally erodes the ability of shipping companies to operate efficiently and profitably, and tarnishes the reputation of the industry.

The shipping industry is relatively susceptible to corruption because of the following unique factors.

Regular port calls and numerous inspections in different countries around the world, distinct sets of archiac law and regulation in local languages, and multiple levels of bureaucracy, among others, often expose the ship captains and crew to demands for illicit payments.

Also, it doesn’t help that small bribes are often deeply embedded in local culture.

Moreover, the probable threats of physical harm and long delays that result in huge cost can add to the pressure to pay bribes.

The Maritime Anti-Corruption Network (MACN) reported that a customs officer accosted one captain and threatened to delay the ship and fine him US$60,000 for an error on the lubrication oil declaration.

He then proceeded to ask for a bribe of US$7,000 to solve the problem.

To show the pervasiveness of bribery, there are incidents occurring even in Singapore, a country with strict regulations, extensive enforcement and heavy penalties.

A recent case in Singapore involved an associate consultant of marine surveying company PacMarine Services Pte Ltd.

On three occasions, the respondent solicited bribes from ship masters in return for submitting false inspection reports that would allow the vessels to enter an oil terminal.

An aggravating factor in this case was that he was responsible for ensuring that vessels were free of high-risk defects before entering the oil terminal.

He ignored this responsibility, understated threats, and sought to illicit bribes of US$3,000 in each incident, thereby putting a significant risk to human lives, the terminal and vessel.

Know the serious consequences

From C-suite management like CEOs and CFOs, to operational crew like ship masters or captains, all staff should be aware that the consequences of paying bribes extend beyond potential prosecution to severe safety risks.

So too, according to MACN, these corrupt demands are bad for shipping companies who stood their ground, as they can lead to delays or other commercial consequences. They are bad for the ports and governments, who acquire a reputation for corruption and have friction in the trading environment.

They are bad for the ships’ captains and crews, who come under pressure to reject demands yet face threats, intimidation, and sometimes violence when they try to do so.

Another issue to note is that acceding to demands for bribes may also constitute an offence under Singapore’s Prevention of Corruption Act and other international anticorruption legislation.

Ship crew and port officials should be aware that even low-level bribery will be pursued by enforcement agencies and prosecutors who are willing to pursue strict penalties to deter future offenders.

Take action now

Anti-corruption compliance is clearly gaining ground in the maritime industry.

Now is the time, more than ever, for shipping companies if they have not already done so, to map out their anti-corruption strategy, come up with an action framework and then execute the plan.

To effect a positive change on the wider industry environment, I encourage shipping companies to also fight corruption through collective action.

This provides an opportunity to understand, communicate and engage with competitors and officials alike.

A stronger collective voice is often louder when speaking with governments, ports, and customs officials to combat ingrained and systemic corruption.

The fight is all about having transparency and integrity, therefore increasing the value of the companies.

In a nutshell, I wish to bring awareness to the fact that such acts are detrimental not only to the companies involved, but also to the industry as a whole.

I encourage CEOs of shipping companies to take the lead in the anti-corruption fight.

And on that note, stay informed, stand firm, and believe in the cause! Talk to you soon!

Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) on Friday (8 March) said 35-year-old Chinese Singaporean, Lim Leong, was charged in court for corruption during a bunkering operation.

He tried to bribe a Marine Surveyor in the employment of Viking Marine Services Pte Ltd (VMS) by offering him an unspecified sum to certify a certain quantity of bunker fuel was supplied to vessel A70 when in fact a lesser quantity of bunker fuel was supplied.

The VMS surveyor rejected the offer; Lim Leong was later charged with one count of corruptly offering gratification.

“The bunkering industry in Singapore is among the largest in the world. It is important to protect the integrity of the industry and to ensure a level playing field for all,” said CPIB.

“Singapore does not tolerate corruption. It is a serious offence to give or attempt to give bribes. Any person who is convicted of corruption can be fined up to $100,000 or sentenced to imprisonment of up to 5 years or to both.”

‘ … this kind of corruption is antithetical to everything that Singapore stands for as it undermines the confidence that if a person needs something such as a permit or licence to do business in Singapore, it will be forthcoming without bribes being paid. It also destroys the notion that business in Singapore is clean and transparent and that rules are there for good reason rather than to give people in whom discretion is vested or upon whom duties are placed, opportunities to have their palms greased and their pockets lined. In such cases, all would-be offenders must be warned that such acts, which undermine legitimate rights, will not be tolerated and will be severely dealt with.’ (Menon CJ in Public Prosecutor v Syed Mostofa Romel [2015] SGHC 117, at para. 30)

A recent case in Singapore, Public Prosecutor v Syed Mostofa Romel, has served to highlight some key lessons for the shipping industry in face of growing anti-corruption enforcement.

The case concerned bribery charges against Syed Mostofa Romel (the respondent), an associate consultant in the marine surveying business of PacMarine Services Pte Ltd. The respondent was responsible for conducting inspections of vessels seeking to enter an oil terminal, which involved ensuring vessels were sea-worthy and free of any high-risk defects; ensuring cargo was properly documented; and ensuring vessels had correct documentation. Where defects were identified during an inspection, vessels would be allowed to enter the terminal and remedial works would be carried out if the defects posed low to medium-risk; however, if defects were classified as high-risk, rectifications would have to be carried out prior to entering the terminal. Regardless of classification, the respondent was responsible for preparing a report and submitting it to his superior.

On three occasions, the respondent solicited bribes from ship masters in return for submitting false inspection reports that would allow the vessels to enter an oil terminal. Chief Justice of Singapore Sundaresh Menon (Menon CJ) allowed an appeal brought by the Public Prosecutor against the sentence imposed on the respondent by a district judge, deciding it was manifestly inadequate and clarifying guidelines on sentencing for bribery and corruption offences.

The respondent was charged with three offences under Singapore’s Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA) – two charges were proceeded with and the remaining charge was taken into consideration when sentencing. The facts of the offences are as follows:

•On March 10, 2014, the Respondent conducted a vessel safety inspection on the MT Torero at Vopak Terminal Banyan Jetty. After the inspection, he informed the ship master and the chief engineer of several high-risk observations which were likely to result in the vessel not being allowed to enter the terminal. The master disagreed with the observations and thought that the defects were minor ones which could be readily rectified. He asked the respondent how he could resolve the situation and the respondent informed him that money would do so. After some negotiation, the master agreed to pay the respondent US$3,000, while secretly reporting the bribe to his superiors.

•On May 27, 2014, a sting operation was launched by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) to catch the respondent in the act of bribery when the MT Torero arrived at the same port. The vessel was deliberately prepared with high-risk defects and the respondent was assigned to conduct its inspection. The ship master was again informed by the Respondent that these could be omitted from his report in return for a bribe, which was paid, and the altered report printed before the respondent was arrested by the CPIB.

The decision by Menon CJ highlights Singapore’s increased efforts to tackle private sector corruption. Although public sector offences typically attract custodial sentences, while private sector cases typically attract fines, this case illustrates that the distinction is not rigid nor is it reflective of the law in Singapore. The respondent was in a position to overstate risks and cause inconvenience as well as unnecessary expense and delay to ship masters unless a bribe was paid. The respondent could also offer to understate risks and in doing so threaten the safety of others in the oil terminal. In combining these two breaches of his duty by overstating the risks and offering to understate them, he could receive financial benefit in the process.

Menon CJ made clear that a custodial sentence is generally expected. Regardless of whether bribery is related to a private or public sector, sentencing will be determined by the severity and nature of the offence, public interest in prosecution, and its potential threat to safety of people and facilities. In this case, the maritime industry’s strategic significance to Singapore was given as a specific aggravating factor in sentencing considerations. The shipping industry accounts for roughly 7 per cent of Singapore’s GDP and provides employment for 170,000 people. Since increased corruption could have a large effect on the nation’s economy, Menon CJ recommended that bribery offences in shipping relating to Singapore be strictly punished, with longer prison terms for offenders. As a result, Menon CJ disagreed with the district judge who had sentenced the respondent to a two months’ imprisonment for each charge and instead sentenced the respondent to a terms of six months’ imprisonment for each charge, which were to run concurrently.

On a global scale, demands for bribes in ports pose a particular threat to the maritime industry. In the case at hand, the respondent was required to ensure that vessels were free of high-risk defects before entering the oil terminal. On two occasions, the respondent ignored his responsibilities and sought to illicit bribes – US$3,000 in each incident. The admittance of unsafe vessels was a significant threat to the people working in the terminal, the terminal itself, the crew of the vessel, and also the vessel itself. Ship masters should be aware that the consequences of paying bribes extend beyond potential prosecution to severe safety risks.

Acceding to demands for bribes may also constitute an offence under the PCA and other international anticorruption legislation. There is no indication in the decision as to whether the master was also charged with bribery. UK and US regimes, as well as the law in Singapore, prohibit giving a bribe unless there is an immediate threat of physical harm (whether to the ship master or the crew). In this case, the facts suggest that the respondent made no threat of death or bodily injury and so the ship master could have safely refused to make payment. The fact that a bribe is first introduced by the recipient does ‘not alter the corrupt purpose of the part of the person paying the bribe’ (US Congress, introducing the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act 1977). It is clear from Menon CJ’s decision that Singapore is willing to pursue individuals for instances of low-level bribery. The sentence imposed on the respondent should be a warning to ship masters against future opportunities to grease palms. The sting operation carried out by the CPIB should also dissuade persons tempted to receive bribes from making such demands.

Anti-bribery compliance is clearly gaining ground in the maritime industry. Corruption dramatically increases the costs of transporting goods by sea and small bribes are often deeply embedded in local culture. Harsher sentencing for offenders is one means of deterring demands for bribes. At the same time, shipping companies need to work together to fight corruption through collective action. Collective action initiatives are increasingly gaining interest from the shipping industry, as they provide the opportunity to engage with competitors and the public sector to combat systemic issues such as demands for small bribes. The World Bank has explicitly encouraged businesses to take part in collective action and funding is available for new enterprises.1 While companies may have ensured that the activities they control reflect good practice, isolated efforts are insufficient to counter institutionalised corruption.

In recent years, there has been a significant uplift in anti-corruption enforcement activity, coupled with increased cooperation between regulators. For the maritime industry, the case of Public Prosecutor v Syed Mostofa Romel reflects increasing stringency against a background of growing concern around the world for anti-bribery compliance. Masters and port officials should be aware that even low-level bribery will be pursued by enforcement agencies and prosecutors who are willing to pursue strict penalties to deter future offenders. At the same time, given the growing attention on graft in the maritime industry, now is the time for shipping companies to think about what they can do to change the wider business environment through collective action. The fragmented nature of the shipping industry makes fighting corruption difficult. The problem demands collaboration in order to put pressure on governments, port officials and the sector as a whole to improve their reputation for transparency and integrity.

This piece was originally published by the TRACE International Blog on 8 May 2015. Republished here with permission.

Last week’s (ed: 28 April 2015) decision by the Chief Justice of Singapore’s Supreme Court entitled Public Prosecutor v Syed Mostofa Romel is important for shipping companies operating in Singapore. The decision regards bribery charges against a local vessel surveyor who on three occasions solicited bribes from ship masters for issuing favorable inspection reports that would allow the ships to enter an oil terminal. Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon disagreed with a district judge that had sentenced the respondent, Syed Mostofa Romel, to a two-month imprisonment and instead argued that given the circumstances the jail time should be extended to at least six months per charge, (at least 12 months). Chief Justice Menon’s explanation may be used in future maritime-related bribery cases in Singapore.

Singapore’s 1960 Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA) applies to both the supply and demand side of a bribery transaction including agents, and is punishable by a fine of up to SGD$100,000 or imprisonment up to five years, or both. The PCA does not contain any exceptions for “customary” payments, including facilitation payments. Any person who is suspected of bribery can be arrested and searched without a warrant by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB). The CPIB can also investigate any bank account or safe deposit box belonging to a suspect of a bribery offence. Given the growing international cooperation in bribery investigations, it is plausible to assume that non-Singapore citizens or residents could be implicated in national investigations with the information being subsequently shared with other national authorities.

The decision contains three main takeaway lessons for those operating in the shipping industry. First, punishment for private sector bribery is just as harsh as that for public sector bribery. Chief Justice Menon argues against the presumption of predominantly non-jail sentences in cases of private sector corruption and refers to the PCA’s enforcement practice, according to which the public interest and the gravity of the offence, among other considerations, determine the sentencing decisions. Chief Justice Menon points out that even though the PCA largely focuses on private sector bribery, it also applies to bribery by “private agents, trustees and others in a fiduciary capacity.” In this particular case the vessel surveyor was a private sector agent without any regulatory and oversight functions that could justify the application of a “public service rationale.” Regardless of whether bribery is related to a private or public sector, the severity of the offence due to its potential threat to safety of people and facilities should justify a longer prison term for the offender, argues the chief justice.

Second, bribery in port can cause severe safety risks. In the case at hand, the vessel surveyor was supposed to have ensured that the vessels had no high-risk defects before entering the oil terminal. If such defects were identified during the inspection, the vessels would have undergone rectifications before being permitted to enter the terminal. On two occasions, the surveyor exaggerated his findings by indicating some non-existing high-risk defects to elicit bribes–US$3,000 in each incident–from the ship masters in exchange for the accurate inspection reports he should have produced. On a third occasion, which was in reality a sting operation organized by the CPIB, the surveyor attempted to elicit a bribe from a ship master in exchange for a report that would not mention the high-risk defects that the inspection identified. (Those defects were intentionally created for the purposes of the sting operation.) Chief Justice Menon argues that a bribery incident that allows a vessel with high-risk defects to enter an oil terminal poses a grave threat to both people working in the terminal and the terminal itself, and therefore should be regarded as an aggravating factor in considering the type and degree of punishment.

Third, acquiescence to extortion demands are also considered bribes. Even though there is no information available as to whether either or both ship masters were accused of bribery, the main international anti-bribery laws prohibit giving a bribe, unless there is imminent threat of physical harm. In this particular case, it appears that no threat of death or serious bodily injury was present, and therefore both ship masters could safely walk away without making a payment. As the U.S. Congress noted when it enacted the 1977 U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the fact that the payment was “first proposed by the recipient… does not alter the corrupt purpose of the part of the person paying the bribe.”

Finally, bribery in the maritime industry as a whole—not just in ports – may be regarded as an aggravating factor in sentencing considerations. Chief Justice Menon maintains in his opinion that the maritime industry is a strategic industry in Singapore that accounts for up to 7% of GDP and provides employment to 170,000 people. Since the ramifications of increased corruption perceptions in Singapore’s shipping industry could have significant detrimental effect on the nation’s economy, one can expect that any bribery incidents involving shipping will be strictly punished, including through longer prison terms for offenders.

This Singapore bribery case, along with other recent legislative, enforcement, and collective action initiatives in the shipping industry worldwide, strongly suggests that anti-bribery compliance is gaining ground. The most challenging perhaps would be to change long-established attitudes towards bribery in the industry that “things are just done that way.” No longer.

As a marine surveyor it may seem you are there to be shot at by just about everyone! Not only may those who have instructed you try and hold you liable if things go wrong but you may find that third parties claim to have suffered as a result of something you have done.

It is, perhaps, the unique position of a marine surveyor, as someone who will produce a report which may be seen and possibly relied upon by parties other than his original client, that has given rise to questions as to the extent of a surveyor's liabilities.

The purpose of this article is to examine briefly the extent of those liabilities and to give what we hope will be some obvious suggestions about how potential problems could be avoided.

The surveyor's duty

You will have been retained by your client either verbally over the telephone, or in writing, or a combination of the two. The written contract may just be an exchange of correspondence or something more detailed.

Whether the terms of the contract expressly say so or not there will be, implied in every contract, a term that the surveyor will carry out his work with the due skill and care of a competent surveyor in the circumstances of a particular case.

The circumstances which will be taken into account by the court will be the extent of the surveyor's instructions from his client. In other words, a court would look at what the surveyor had been asked to do. Oral evidence will often be important.

Whether the survey is a pre-purchase inspection of a vessel, an on or off-hire survey in relation to a charterparty, or a cargo survey, it is in the surveyor's interests to define for his clients, at the very outset, the precise extent of the work he is to undertake and specifically what matters are to be excluded. We have seen a number of disputes between a surveyor and his client as to the extent of the work that had been agreed to be carried out where the client's expectations invariably exceeded those of the surveyor! To avoid such difficulties we cannot emphasise enough the need to be specific about the extent of the work to be undertaken.

Quite apart from the duties the surveyor will owe under his contract with his client, he also owes him a duty of care under the law of tort. It is for this reason that many claims are framed in negligence as well as in breach of contract. The extent of the duty is the same as in the contract, namely to carry out the job with the reasonable skill and care of a competent surveyor in the circumstances of the case.

Although the duty is the same in both contract and tort, there is a legal difference when it comes to the question of a breach of those duties. There may be differences in damages where a claim is framed in contract rather than in negligence. The most significant difference is, that, under his contract, the surveyor owes the duty only to his client whereas a duty of care is not necessarily so confined. It is, therefore, important to see if the law allows the surveyor to be liable to someone other than his own client.

To whom is the duty of care in tort owed?

There is, of course, no question that the duty of care extends to the surveyor's client but, given that the duty is independent of a contractual relationship, need the surveyor fear attack from any other quarter?

The law of negligence is part of that body of English law that is under continual review by the English courts. The courts are bound by a system of precedent formed by previous legal decisions going back over many years and it is up to the courts to develop that precedent as new factual situations come before them. As far as a surveyor's task is concerned he will be making statements, usually in a written report, upon which someone is going to rely and a claim will usually arise when the party relying on those statements claims to be out of pocket as a result of them. The courts have always been reluctant to restrict situations in which liability can arise for financial loss through statements negligently made. They have done so by restricting the duty of care to situations where a ''special relationship'' exists between the innocent party and the wrongdoer. Under this restriction liability would arise only where the wrongdoer was aware of the transaction that the innocent party had in mind and knew that the innocent party would rely on his advice.

It may seem, therefore, that a surveyor, who knows his report may be seen and relied upon by a third party, would have a liability to that third party if he suffered financial loss.

Fortunately for surveyors and those involved in a similar advisory capacity, the courts have further restricted the duty of care as highlighted by the 1990 landmark case of Mariola Marine Corporation - v- Lloyds Register of Shipping ("Morning Watch"). In that case a Lloyds surveyor had given an 80 foot steel hulled motor yacht, the "Morning Watch", a periodical special survey and had passed her as 100 A1. The surveyor knew that a purchaser was interested in the yacht at the time and that purchaser decided to rely on the class certificate as confirming the yacht's good condition at the time he purchased her. Subsequently after delivery the owner discovered substantial defects with the yacht which were enough to take her well outside Class. The purchaser looked to Lloyds to reimburse him for the substantial repair costs. He had, after all, relied on the Lloyds surveyor's report, as the surveyor well knew.

Lloyds declined to reimburse the purchaser and the case went to court. The purchaser argued that the necessary "special relationship" existed and the court accepted that the surveyor had been negligent. The court, however, decided that Lloyds did not owe a duty of care to this purchaser, or indeed to any future purchaser of a vessel who was likely to rely on a pre purchase classification certificate issued by Lloyds. Whilst it would appear that public policy played no little part in the decision it produced an important precedent greatly limiting the possible liability of a surveyor whose reports may be relied upon by those other than his client.

Conclusion

Although the range of possible parties from whom a Surveyor might face claims is limited, he would still owe a duty to his client.

To minimise the likelihood of such a claim the surveyor's starting point must be a careful definition at the outset of the services to be provided. Particular consideration should also be given to making quite explicit in the survey report any limitations to the investigation to which the surveyor had been subject. He should also advise where further investigation by the client or a specialist expert would be considered prudent. Where a client may be present at the time of survey then no reliance should be placed on any oral comments made to the client which could later be denied. Instead it is important to ensure that everything found at the time of the survey finds its way into the written report.

Hw Global IMO 8914037 Flag: Panama built: 1990(ShipSpotting.com)

Lucky Future IMO 8822260 Flag: Panama built: 1989(ShipSpotting.com)

今度はシエラレオネ船籍の大型船が出港停止命令を受けた。 シエラレオネ船籍船は日本に麻薬を運んできたり、 不適切な免状の船員が操船する船が日本の内航船に衝突して、衝突された船に保険金が支払われずに泣き寝入りの状態になった。 大型のサブスタンダード船が日本で大きな損害を与えるまで時間的にそう遠くないかもしれない。

SOUTH HILL 2 IMO 8412467 Flag: Sierra Leone (Ex-North Korea) built: 1984(ShipSpotting.com)

Oriental Sunny IMO 8318817 Flag: Cambodia built: 1985(ShipSpotting.com)

カンボジア船籍船 AN FENG 8 IMO 9365726の無責任な放置に成功したケースで 気を良くした中国船主が増えたのか、国際船級協会連合(IACS)でない検査会社(2流、又は3流)が 検査した船が大型化している。これまでは総トン数1万トンを超えた船はほとんど見られなかったし、日本にもほとんど入港しなかった。しかし、このような 船(サブスタンダード船の可能性が高い)が座礁したり、沈没したらどれほどの被害が出るのか?とてつもない額である。 ベリーズ船籍貨物船「GOLD LEADER」(総トン数1466トン、日本船籍内航船の時の総トン数683.96トン)が沈没した時の被害は約52億円。(参照:【第171通常国会】衆議院・国土交通委員会) 総トン数1500トンで52億円の被害である。総トン数1万トンの船の被害はとてつもない額になることが予測される。船の燃料タンクの容量も比べ物にならないほどに 大きい。保険に加入しているから安心と思っていたら大間違い。保険会社は船又は船員の免状や操船に問題があることを理由に支払いを拒否する可能性が非常に高い。 サブスタンダード船はいろいろな面で保険会社が支払いを拒否する問題を大きく抱えている。保険の加入は 気休めである。大きな損害を出す海難を起こす前にこのようなサブスタンダード船の厳しい検査を行わなければ とんでもない事になることを忠告します。このサイトを見た方で、利害関係がある人は行政に相談して早急の対策を求めてください。いつ大きな損害が出るかは 運次第です。

【ニューヨーク=上塚真由】国連安全保障理事会で、対北朝鮮の制裁決議の履行状況を監視し、制裁逃れを調べる北朝鮮制裁委員会の専門家パネルの年次報告書が15日、公表された。北朝鮮は、公海上で船から船へ石油精製品を移し替える「瀬取り」の手口を巧妙化させているほか、違法な金融取引や、内戦が続くシリアとの軍事協力を活発化させている実態も明らかになった。

▽国際的なブローカー

「北朝鮮は、国際的な石油供給網を駆使し、外国人と共謀、海外企業の登記や国際銀行システムを悪用して、直近の安保理決議も無視している」

292ページに及ぶ報告書の冒頭でこう指摘し、悪質な制裁逃れの実態を批判。とくに注目しているのは石油精製品などの密輸手段となっている「瀬取り」だ。

報告書では昨年10月以降の「瀬取り」の手口として、船名を偽装する▽北朝鮮の国旗を白く塗りつぶす▽夜間に行う▽位置や速度を他の船に電波で知らせる船舶自動識別装置(AIS)を切る-などがみられるとした。

また、「瀬取り」に使用された香港やパナマ籍の船舶などの背後には「台湾を拠点としたネットワーク」があると指摘。台湾の男がマーシャル諸島などで登記した会社を通じ、船舶を所有したりチャーターしたりしていた。また石油精製品の調達には、香港やシンガポールに登記がある企業が関わっていたとし、「国際的なブローカーのネットワークに加え、無意識のうちに加担している貿易会社や石油会社によって、数百万ドルの違法なビジネスが生み出されている」などと注意も呼びかけた。

▽活発な軍事取引

報告書では長年、軍事協力を行っているとされる北朝鮮とシリアの関係が強化されていることもうかがえた。

2016年11月に、北朝鮮の国防科学院の傘下にある弾道ミサイル開発の技術者グループがシリアを訪問。その他にも同年には2度にわたって北朝鮮の技術者らの訪問が確認され、シリアの軍事施設に宿泊したこともあったという。また、加盟国からの情報として、北朝鮮の技術者が、首都ダマスカスなどにある化学兵器やミサイル開発施設で活動を続けていることも報告された。

このほか北朝鮮は、12年から17年に貨物をシリアへ輸送する取り引きを40件以上行っていた。貨物の中には、化学兵器製造施設で使われることがある特殊なタイルが含まれていた。

▽金融取引も

金融制裁の分野でも制裁の「穴」が指摘された。

北朝鮮の金融機関の代表者30人超が中東やアジアを自由に行き来して、銀行口座を保持して、違法な金融取引を続けていると指摘。昨年は中国、リビア、ロシア、シリア、アラブ首長国連邦(UAE)での活動が確認されたという。

報告書では「北朝鮮の不正な活動や、加盟国の適切さを欠いた行動によって、金融制裁の効果が損なわれている」とし、加盟国に制裁の履行徹底を呼びかけた。

【ソウル=峯岸博】韓国の聯合ニュースは31日、北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いのあるパナマ船籍の石油タンカーを韓国当局が検査していると報じた。韓国西部の唐津港に留め置かれており、船員の大半が中国人とミャンマー人だという。

国連安全保障理事会は北朝鮮の核・ミサイル開発を封じ込めるため、石油精製品の輸出を規制する制裁を採択した。今回の船舶間の移し替えが事実なら、制裁逃れの韓国政府による確認は29日に発覚した香港籍の貨物船に続き2例目。

聯合ニュースは31日、北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いのあるパナマ船籍の運搬船を、韓国西部の港で当局が調べていると伝えた。事実なら、韓国政府による北朝鮮船への移し替え確認は、南部の麗水港で検査した香港船籍の貨物船「ライトハウス・ウィンモア」に次ぎ2例目となる。

聯合によると、韓国当局は「北朝鮮との関連が疑われる船舶」としてパナマ船籍の「KOTI」号を調べている。船員の大部分は中国人やミャンマー人。出港を許可せず、調査には関税庁や情報機関の国家情報院が当たっているという。

国連安全保障理事会は9月、海上で北朝鮮の船に積み荷を移すことを禁止する制裁決議を採択した。しかし、既に韓国が確認した香港船籍の貨物船のほか、ロシア船籍の複数のタンカーも過去数カ月間に北朝鮮の船舶に石油精製品を移し替えたとの報道もある。(共同)

【ソウル聯合ニュース】北朝鮮船舶に石油精製品を移し替えた疑いで、パナマ船籍の石油タンカー「KOTI」号(5100トン)が韓国西部の平沢・唐津港で関税庁など関連機関の検査を受けていることが31日分かった。平沢地方海洋水産庁が明らかにした。

乗船していたのは中国人とミャンマー人が大部分で、関税庁と情報機関・国家情報院が合同で調べを進めているもようだ。

韓国政府は29日にも、香港籍の船「ライトハウス・ウィンモア」号が10月に公海上で石油精製品600トンを北朝鮮船舶に移し替えたことを確認したと発表した。11月に韓国南部・麗水に寄港した同船は検査を受け、抑留されている。

国連安全保障理事会は9月、海上で北朝鮮船舶へ積み荷を移すことを禁止する制裁決議を採択している。パナマ籍の船の嫌疑が確認されれば、この制裁決議への違反で韓国当局が船舶を摘発するのは2度目となる。

【ニューヨーク=水野哲也】武器の運送に関わったとして国連安全保障理事会の制裁を受けた北朝鮮の貨物船運航会社が、本来は船を運航できないのに、制裁発動後、船名や運航会社名を変えて運航を続け、制裁を逃れていたことが25日、読売新聞が入手した国連北朝鮮制裁委員会の専門家パネル報告書で明らかになった。

英国の北朝鮮大使館職員が手続きしており、外交官も関与した制裁逃れの実態が明らかになった。

この会社は「オーシャン・マリタイム・マネジメント・カンパニー(OMM)」。同社は、キューバで分解された戦闘機やミサイル部品を積み込み、パナマ運河を通過しようとして2013年7月に拿捕だほされた貨物船を運航。北朝鮮への武器の輸出や移動を禁じた安保理決議に違反したとして、昨年7月、資産凍結などの制裁が発動され、貨物船を運航できなくなった。

ところが、報告書によると、制裁発動直後、同社が運航していた14隻のうち13隻の船名が次々と変わり、所有会社や運航会社名も変更されて引き続き運航されていた。国際海事機関(IMO)に対し、新たな名前や会社名を届ける手続きはロンドンの北朝鮮大使館職員が行っていたという。

北朝鮮の大手海運会社が国連安全保障理事会の制裁を受けた昨夏以降、自らが運航に関与した貨物船の船名や所有会社を次々と変更していたことが、25日わかった。対北朝鮮制裁の実施状況を監視する安保理の専門家パネルは、船名などの変更が制裁逃れの手段になっているとみて、制裁の強化を勧告している。

北朝鮮は、一連の核実験やミサイル発射を受けた安保理決議で、大量破壊兵器関連の物資技術や通常兵器の輸出入禁止、ぜいたく品の禁止、団体・個人の資産凍結など広範な制裁を受けている。

専門家パネルは今回、これまでの調査結果を報告書にまとめ、北朝鮮の海運会社オーシャン・マリタイム・マネジメント社(OMM社)を取り上げた。同社は、戦闘機を大量の砂糖袋の下に積んだ状態でパナマ政府に拿捕(だほ)された貨物船「清川江(チョンチョンガン)」の運航に関わったとして、昨年7月に安保理の下部組織「北朝鮮制裁委員会」から資産凍結などの制裁対象にされていた。

日本に入港する サブ・スタンダード船 が登録されている国を紹介します。 偽造書類 や 密輸船 問題で船の国籍が出てくるので聞いたことがあるかもしれません。日本は 船が登録されている国の責任で管理及び監督すべきだと言っています。しかし、 現実は無理。 出来ないから、又は、実行しないから、それを承知で 利用している場合がある。 カンボジア籍船が典型的な例だ。

カンボジア政府は管理および監督を放棄し、全ての責任は船の所有者である船主と船の登録の権限を持つ韓国プサンにあるInternational Ship Registry of Cambodia (ISROC) と 言うのだ。このような発言を行っても、TOKYO MOUや日本を含む各国のPSC の対応は鈍い。まるで、カンボジア籍船に対して大目に見ているようだ。 日本は欠陥船根絶で監査制度を国連の国際海事機関(IMO)に提唱。 日本に入港する外国船に対して厳しく検査している印象を与えれいるが、実際は 海保や外国船舶監督官による検査は甘い。 結果として海難を起こしやすいサブ・スタンダード船 が座礁し撤去費用が船主の負担になれば放置されるのである。船の所有者は船を放置し、撤去費用を支払わないことにより損失を最小限に出来る。 船が放置された地方自治体は困るし、撤去費用の被害を被るが、船主には関係にないことだ。価格が安いサブ・スタンダード船は 問題が多い船員達でほとんど維持費をかけることなく安く運航が出来るし、問題が起きれば放置し、逃げることが出来る。まさに一石二鳥でなく、一石三鳥なのだ。 最近の例では青森県の座礁船である。

多くのサブ・スタンダード船が登録されている、又は、されていた旗国は次の通りである。

★カンボジア籍船

:以前はホンジュラスやベリーズが有名でした。現在は、質の悪い船/登録されている隻数

では世界で一番だと思います。

★カンボジア籍船

:以前はホンジュラスやベリーズが有名でした。現在は、質の悪い船/登録されている隻数

では世界で一番だと思います。

★モンゴル籍船

:カンボジアの後に出来ました。以前、カンボジア船を登録した会社が登録業をしている。

★モンゴル籍船

:カンボジアの後に出来ました。以前、カンボジア船を登録した会社が登録業をしている。

★ツバル籍船

:日本で問題と見られている国籍では、一番新しい。以前、カンボジア船を登録した会社が

登録業をしている。

★ツバル籍船

:日本で問題と見られている国籍では、一番新しい。以前、カンボジア船を登録した会社が

登録業をしている。

![]() ★グルジア籍船

:日本で出港停止命令を受けた船舶が増えた。ツバル籍船の次になるのか。

★グルジア籍船

:日本で出港停止命令を受けた船舶が増えた。ツバル籍船の次になるのか。

連絡先の情報については、

AMSA(オーストラリア)のHPを参考にしてください。

★シエラレオネ籍船: 北九州で大量の麻薬が見つかり、船主は行方不明になり船が放置された事件に認知度がアップ。また、東京・伊豆大島沖で2013年9月、丸仲海運が所有する貨物船「第18栄福丸」が中国企業所有のシエラレオネ籍船貨物船「JIA HUI」と衝突し、栄福丸の乗組員六人が死亡した事故でさらに注目を集める。

★シエラレオネ籍船: 北九州で大量の麻薬が見つかり、船主は行方不明になり船が放置された事件に認知度がアップ。また、東京・伊豆大島沖で2013年9月、丸仲海運が所有する貨物船「第18栄福丸」が中国企業所有のシエラレオネ籍船貨物船「JIA HUI」と衝突し、栄福丸の乗組員六人が死亡した事故でさらに注目を集める。

![]() ★トーゴ籍船:日本ではまだ少ない。

★トーゴ籍船:日本ではまだ少ない。

![]() ★パラオ籍船:日本でも見られるようになった。

★パラオ籍船:日本でも見られるようになった。

国際条約に基づき国際基準を満たした証明として証書(車検証のようなもの)が発行される。これを船舶に

所持をしていないと、国際航海ができない。PSC(外国船舶監督官)の検査は一般的に書類チェックから始まる。

世の中には抜け道がある。検査会社の中には、船に問題があっても証書が発行する。報告書には、もちろん、問題は明記されない。修理、

部品の交換や検査の省略により、コストが下がる。そして、お金を儲けるのである。

例えば日本では

原発の検査の問題で電力会社がどのように検査を通すかとの点に時間やコストを費やしている。問題が存在する状態で、検査をごまかしてもらう、又は、指摘を受けずに検査に合格すれば、修理の費用も浮く、修理する期間がなくなる、又は、短縮できることにより、稼働率が

上がり儲けが増える。

最低限の資格を持っているが実際の経験や教育が十分でない船員を使うことにより、人件費が抑えれらる。 もっとひどい場合もある。ISMコード(ISO:国際標準化機構の海運バージョン)の 要求を満たしていることを証明する証書を発給するために外部審査が行われるが、船員の免状に問題があっても証書が発給されることが前提の外部審査では チェックさえも行われずに不備なして証書が発給される。お金さえ払えば、問題や不備があっても船を運航するための証書が取得できる。 このようなメリットがサブ・スタンダード船にある。厳しい基準や船員の評価が高い海運会社だと資格だけで採用しないし、問題が発覚すれば次の契約はない。 待遇が良い海運会社で働きたくても実力が伴わない船員は待遇が良くない、又は、給料が低い会社で働く。結果として同じ状態の船舶でも、躁船する船員の質により海難を起こす確率は違ってくる。座礁事故を起こしても、お金が無いから撤去出来ないと船を放置する事も出来る。 例えばなしではなく、日本で実際の起きている。一件や二件の問題ではない。 船舶油濁損害賠償保障法は期待されたようには機能しないざる法であることが明確になった。船舶保険 (P&I) に船舶が加入していても、船員の免状に問題があれば保険はおりない。カンボジア籍船MING GUANG が良い例だ。日本の対応が甘いから、現在まで放置される船はなくならない。

モラルを気にしないのであれば、 サブ・スタンダード船が一番コストを抑えられる。 最悪のケースで船が座礁すれば、放置すればよい。 高学歴の東京大学の教授達が、非常識な行為を行い、お金を流用していたケースがある。厳しい取締がないと秩序は守れないのが現状だ。 高学歴だから、公務員だから、 検査官だからと言った考え方は現実的でない。。 耐震強度偽造 では、性善説で言い訳をしているが、そんな理由など通らないと思う。

これは 日本のPSC(外国船舶監督官) を含むアジアのPSCが問題点を指摘していない(出来るだけの知識と能力がない)現状が存在するから成り立つ。 国際船級協会連合(IACS)の 船級規則で遠洋区域(Ocean Going)の要求を満足する内航船などほとんどありません。 船の国籍を選べば、 PSC(外国船舶監督官) が問題を指摘しない現状では逃げ道があるのです。 検査会社が検査を見逃してやり、お金と引き換えに証書を発給するから多くの船が日本に入港出来るのです。 事実を知らないから、上記のような発想が出来るのたろう。

海運局はISO 9001を取得している。簡単なチェックリストを作成すれば効果的に サブ・スタンダード船 を減らすことが出来る。しかし、そのようなチェックリストを作成していない。そして サブ・スタンダード船の不備を今でも指摘できない状態だ。

産地偽装問題と同じで、正直者がばかを見るのが現在の日本。 外国人に対して強い対応が出来ない日本の公務員が生み出した問題だ。 これを読んだ人達の中には割り切れない矛盾を感じる人がいるだろう。しかし、これが現実だ。 外国航空会社が日本の地方空港に参入するケースが増えています。 「国土交通省が、来年度予算の概算要求に『外国航空機安全対策官』の配置を、新規施策として盛り込みました。」 11/01/07(京都新聞) と新聞に書かれている。 PSC(外国船舶監督官) と同じレベルなら外国航空機安全対策官による検査をしないよりはましだ。しかしはっきり言って、空の安全は守れないだろう。 中国が航空機の生産を始め、アメリカの会社が既に発注したとのことです。中国で建造された船に乗っているドイツ人船長が言うには、 中国建造の船に乗るのは問題ないが、中国製の飛行機は空飛ぶ棺おけなので絶対に乗らないと言っていた。 現実を知らない日本人は大惨事が起こるまでは安心して格安の外国航空会社の飛行機に乗るだろう。

下記の海難に対する運輸安全委員会のコメントは変わり行く環境を理解していない証拠だと思う。船の品質に問題があっても検査に通る事実を知らない。 まあ、大手の海運会社や予算さえ取れれば良い船を要求する官庁関連船を発注する役所での勤務経験しかなければ理解できない次元であるかもしれない。

関門海峡で昨年7月、天津港発京浜港行きコンテナ船

ソン・チェン号」(中国船籍、9683トン)

「が座礁する事故があり、運輸安全委員会は26日、航行中のかじ脱落が原因とする報告書を公表した。脱落は国内有数の年5万隻が通過する関門航路内で起き、操船不能となった同船は、対向船舶の航路を横断、他船と衝突の危険もあった。

かじ脱落による商船の海難事故について、安全委は「聞いたことがない」と話している。

報告書によると、09年7月28日午後4時41分ごろ、幅0.5~2.2キロの関門航路を日本海側から入り、右側航路を時速約22キロで航行中の同船内にかじの脱落を示す「バシャーン」という音が響いた。同船は自然に左に回り、対向船舶が航行する左側航路にはみ出す。海上保安庁が無線で警告したが、同船はいかりを下ろすなどしても止まらず、左側航路横断後の同51分、山口県下関市沖の浅瀬に乗り上げた。

船体を調べたところ、かじを固定するナットのゆるみを防ぐ部品を取り付けた跡がなかった。船体とかじの接続部分には、海水流入を防ぐ仕切り板がなく、塩水がナット周辺を劣化させた可能性もある。【本多健】

|

| |

|---|---|

| Ship Name: | BLUE STAR |

| Type of Ship: | CONTAINER SHIP |

| Flag: | LIBERIA |

| IMO: | 9132521 |

| Gross Tonnage (ITC): | 7111 tons |

| Year of Built: | 1997 |

| Builder: | QIUXIN SHIPYARD - SHANGHAI, CHINA |

| Class Society: | LLOYD´S SHIPPING REGISTER |

| Manager & owner: | FLYING LEAF SHIPPING - HONG KONG, CHINA |

26日午後1時頃、北九州市と山口県下関市に面した関門海峡で、中国船籍のコンテナ船「HASCO QINGDAO」(7111トン、21人乗り組み)がエンジントラブルで航行不能になり、約10分間にわたって約1・2キロ漂流した。

他の船舶との衝突事故には至らなかったが、門司海上保安部は「大惨事を招く危険性があった」とし、乗組員から事情を聞いている。

同保安部によると、エンジンが止まった直後に船が何度も汽笛を鳴らしたため、約2キロ離れた同保安部で職員が漂流に気づいた。巡視艇など5隻が急行し、ロープやいかりを使って船を止めた。男性船長は「エンジンが突然止まった」と話しているという。

現場は関門海峡の中でも幅が約500メートルと特に狭い早鞆瀬戸(はやとものせと)。1日約550隻が往来する。当時は船の数も少なく、大きな影響はなかったが、8ノット(時速約15キロ)の速い潮流に乗り、航行不能のまま関門橋の下を通過していた。同保安部は「発生場所や時間帯など幸運が重なった」としている。

コンテナ船は23日に中国・上海を出港し、北九州市門司区の「太刀浦コンテナターミナル」に入港する予定だった。

26日午後1時ごろ、関門海峡を航行中の中国籍のコンテナ船(7111トン)が突然停止するトラブルがあった。潮流の影響で、船は約1キロにわたって西に流された。近くでは当時、船舶数隻が往来していたが、事故はなかった。門司海上保安部は故障とみて、乗組員に事情を聴いている。

海保によると、コンテナ船は中国・上海を出港し、門司区の太刀浦コンテナターミナルに向かう途中。コンテナ船が頻繁に汽笛を鳴らしているのに海保が気づき、巡視艇を現場に急行させ、周囲の警戒に当たった。巡視艇やコンテナ船が手配したタグボートが近くの海岸までえい航した。

=2014/11/27付 西日本新聞朝刊=

運輸安全委員会は問題のある検査会社の情報を持っていないのであろう。問題を把握していれば可能性は否定できない。運良く大事故が起きていないだけである。

外国では、 サブ・スタンダード船 を利用しないように呼びかけているようであるが、 日本では、あまり聞いたことがない。日本でも、この サブ・スタンダード船 を利用している会社や人間がいる。

社団法人日本船主協会のホームページ に F:サブスタンダード船排除 サブスタンダード船排除のプロセス などが書かれている。良いことばかりが書かれている。たぶん、良い船主を前提として書かれている と思う。

良い船主/管理会社であれば、検査された時に運悪く船舶に問題があるかもしれない。しかし、所有している船舶や 管理している船舶のほとんどに問題があることはない。船主に問題があれば、よほど良い委託料を 払っていなければ良い管理会社は離れて行くだろう。まあ、現実的には船に費用をかけない船主は、 船の管理にもお金を掛けないから、悪い船主=良い船舶管理会社の関係は成り立たないだろう。

日本で多く利用されるケースとしては、中古船の輸出の場合である。 特に船舶が内航船(国内の航行のみ)の場合は、国際条約を満足しない。そこで、船舶の国籍を日本から 監督(監査)が甘い国(旗国)に変える。そして、取締りのない 日本から出港していくのである。 座礁したらどうなるのか。 日本が負担し、結局は、税金として日本国民の 負担となる。 多くの国民はこのことに関して知らない。

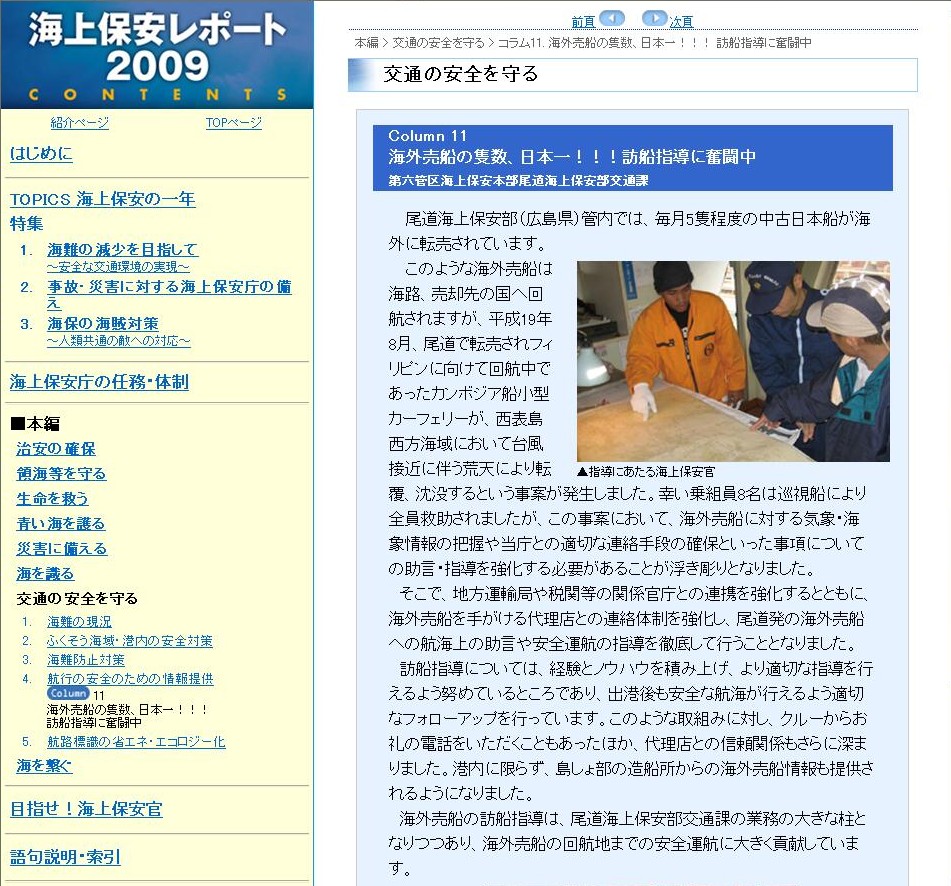

途中で事故を起こす船舶も少なくない。 最低限の装備をする船舶は、良い方である。 いろいろな設備が不足の状態で、出港する船舶が多くいる。 運が悪ければ沈没したり、船員が命を落とす。 中には日本籍の時に名前を書いたままで、出港していく。 税関の職員の中には問題があるのを知っているが、 関係ないので係わらない。 日本では、国土交通省のPSC又は、保安庁が担当である。 お互いが協力し合えば、状況はよくなるのだあろうが、私が知る限りではあまり活動的でない。下記の記事には疑問な点が多くある。個人的には詐欺的な広告と同じだと思っている。

海外売船の隻数、日本一!!! 訪船指導に奮闘中

第六管区海上保安本部尾道海上保安部交通課

海上保安レポート 2009年版

尾道海上保安部(広島県)管内では、毎月5隻程度の中古日本船が海外に転売されています。

このような海外売船は海路、売却先の国へ回航されますが、平成19年8月、尾道で転売されフィリピンに向けて回航中であったカンボジア船小型カーフェリーが、西表島西方海域において台風接近に伴う荒天により転覆、沈没するという事案が発生しました。幸い乗組員8名は巡視船により全員救助されましたが、この事案において、海外売船に対する気象・海象情報の把握や当庁との適切な連絡手段の確保といった事項についての助言・指導を強化する必要があることが浮き彫りとなりました。

そこで、地方運輸局や税関等の関係官庁との連携を強化するとともに、海外売船を手がける代理店との連絡体制を強化し、尾道発の海外売船への航海上の助言や安全運航の指導を徹底して行うこととなりました。

訪船指導については、経験とノウハウを積み上げ、より適切な指導を行えるよう努めているところであり、出港後も安全な航海が行えるよう適切なフォローアップを行っています。このような取組みに対し、クルーからお礼の電話をいただくこともあったほか、代理店との信頼関係もさらに深まりました。港内に限らず、島しょ部の造船所からの海外売船情報も提供されるようになりました。

海外売船の訪船指導は、尾道海上保安部交通課の業務の大きな柱となりつつあり、海外売船の回航地までの安全運航に大きく貢献しています。

尾道市の尾道港を経由して国内の船主から海外へ売り渡される中古の貨物船やタンカーの数が急増している。港周辺に修繕ドックや船員の日用品がそろうスーパーが集積する利便性が高いうえ、景気の低迷で国内の船主が船を手放す動きが加速している。年間数億円の外貨が流れ込む国内有数の売船市場を形成している。

同市東御所町から同市新浜までの約700メートルにわたり、船尾の船名を漢字からアルファベットに書き換えられた売船が並ぶ。大半が700トン未満の小型船だ。引き取ってインドネシアへ運ぶ日本人の船長男性(70)は「尾道は船員の滞在に便利。船内で使う冷蔵庫も買った」とほほ笑んだ。

市港湾振興課によると、売船の年間係留件数は、データが残る2008年度は70件だった。09年度は123件に急増。10年度は9月末時点で既に59隻を数える。

海外へ船を売る場合、国内の船主が取引をする港に船を運んで係留する。代理店が契約と税関手続きを代行。買い主が派遣した船員に船を引き渡す。

代理店によると、景気低迷の影響で、国内の船主が船を手放すケースが急増。インドネシアや中国などの船主が買い求めるケースが増えているという。

代理店の経営者男性(47)は「福山税関支所尾道糸崎出張所は手続きに慣れている。修繕ドックがあり、艤装(ぎそう)品もすぐ手に入る。尾道を取引場所に指定する買い主が多い」と明かす。

尾道港の立地も人気の背景にある。徒歩圏内には船員が泊まるホテル、食料や燃料を買い込めるスーパーやガソリンスタンドがそろう。JR尾道駅や広島空港などがそろい、船員の交通の便も良い。

船員は係留中に地元で長い航海の物資を調達する。1船につき食料費は数十万円、燃料費は数百万円になる。係留件数を考え合わせると、年間数億円相当の外貨が尾道で消費されるとみられる。

尾道第一ホテル(新浜)の高橋優子マネージャーは「海外の船員の宿泊が10人を超すこともある。売船の集積が地域経済に与える効果は大きい」と話している。

【写真説明】尾道港の岸壁に係留する売船。出発に備えて海外の船員(右下)が船名の塗り替え作業をしている

しかしながら、以前は見られなかったが、輸出(出港)前に外国船の検査を行い、不備が あれば出港させないケースが見られるようになった。(安全の為に必要)参考資料 もちろん、問題のある状態で、税関の輸出許可を得て、 出港していく船舶は後を絶たないが。

過去にも尾道港から出港した船が座礁したり、行方不明になっている。 海上保安職員達が厳しく対応していたらこのような海難は起きなかったかもしれない。尾道港を出港してから1カ月以上たった、たぶん、船は沈没したのだろう。

売却先のフィリピンへ運ぶため広島県尾道市の尾道港を出た漁船「MANDAI MARU」(108トン、日野冨士夫船長ら6人乗り組み)が、昨年12月22日から連絡が取れなくなっていることについて、運搬を依頼した宮城県多賀城市の船の売買仲介業の男性(45)が3日、朝日新聞の取材に答えた。携帯電話が通じない海域にいる可能性を指摘しつつも、状況を確認するため5日にフィリピンに向かう考えを示した。

男性によると、乗組員の阿部要さん(66)=同県東松島市=は、東日本大震災の津波で自宅が被災。現在は、元の場所で自宅を再建したという。船長の日野さん(70)=同県石巻市=とともに航海の経験が豊富なベテランで、2人にはこれまでも外国への船の運搬を任せたことがあったという。

男性は船の出発前に、造船会社に依頼して、転覆すると自動でSOSを発信する装置や、予備の発電機などを設置。救命用のボートのほか、飲料水や食料なども十分に積んで、船は12月18日、尾道港を出発した。整備に時間がかかり、出発は予定より4日遅れたという。

フィリピンで売却されるため広島県尾道市の尾道港を出た漁船「MANDAI MARU」(108トン、日野冨士夫船長ら6人乗り組み)が、昨年12月22日から連絡が取れなくなっている、と第11管区海上保安本部(那覇市)が1日、発表した。11管と10管(鹿児島市)の航空機計3機が2日朝から沖縄県の東側海域と鹿児島県奄美大島付近を捜索している。

11管によると、1日午後4時40分ごろ、船の売買仲介業者「松島海運」(宮城県多賀城市)から通報があった。船は尾道港を12月18日に出港。船の航行能力から、フィリピンのミンダナオ島には今月2日か3日に到着する予定だと11管はみているが、着いていない。松島海運が22日午前10時ごろ、船に電話したときは、鹿児島県の奄美大島沖を航行中と言っていたが、その後連絡が取れなくなった。遭難信号は受信されていないという。

乗船しているのは、日野さん(70)=宮城県=、阿部要(もとむ)さん(66)=宮城県東松島市=、吉村喜登志(きとし)さん(80)=札幌市=、伊藤博昭さん(77)=北海道稚内市=、田端善弘さん(78)=静岡県焼津市=、竹内誠秦(しげひろ)さん(75)=東京都。

広島県からフィリピンに向かっていた日本人6人が乗った中古の漁船と、先月22日を最後に連絡が取れなくなりました。

漁船はフィリピンの業者に買い取られる予定だったということで、海上保安本部は、2日の朝から、捜索に当たることにしています。

連絡が取れなくなっているのはツバル船籍の漁船、「MANDAI MARU」(108トン)です。

第11管区海上保安本部によりますと、この漁船は先月18日、広島県尾道市の尾道港を出港し、フィリピン・ミンダナオ島南部のジェネラルサントス市に向かっていました。

しかし、先月22日に「奄美大島の近くを航行している」との電話があって以降、連絡が取れなくなっていて、入港予定の25日を過ぎてもフィリピンに到着していないということです。

漁船には、船長の日野冨士夫さん(70)を含む日本人6人が乗っていて、漁船は宮城県の仲介業者を通してフィリピンの業者に買い取られる予定だったということです。

この漁船からの遭難信号は現時点で確認できておらず、海上保安本部は、到着予定が大幅に遅れ、何らかのトラブルがあった可能性があるとして、2日の朝から、航空機を出して南西諸島東側の海域での捜索に当たるほか、フィリピンや台湾の当局にも捜索への協力を呼びかけています。

広島県からフィリピンに向かっていた漁船と連絡が途絶え、乗っている日本人6人の安否がわからなくなっている。

海上保安本部によると、行方がわからなくなっているのは、ツバル船籍の漁船「MANDAI MARU」。

漁船は、12月18日、広島・尾道市を出港し、25日にはフィリピンのジェネラルサントス市に入港予定で、22日を最後に連絡が取れておらず、乗っている日本人の男性6人の安否がわからなくなっている。

海上保安本部は、2日にも航空機で捜索を始める。

26日午前9時45分頃、鹿児島県・屋久島の宮之浦港の北約11キロの海上で、広島県・尾道港からインドネシアに回航中の旅客船「MASAGENA(マサゲナ)」(全長72メートル、833トン、12人乗り組み)から「荒天のため機関室が浸水し、電気が止まった」と第10管区海上保安本部に無線連絡があった。自力航行できなくなり屋久島方向へ漂流している。海保のヘリコプターが午後0時半頃、現場に到着し、乗組員の救助活動を始めた。

10管によると、乗組員はいずれもインドネシア人で、けが人はない模様。

広島県尾道市港湾振興課などによると、船は四国フェリー(高松市)が所有していた「第五しょうどしま丸」で、建造は1988年。今年2月まで岡山市と小豆島を結ぶ定期航路に使われていたが、新船導入に伴い、今月20日にインドネシアの会社に売却された。25日朝、尾道港を出港し、同国に運ぶ途中だったという。

26日午前9時45分ごろ、鹿児島県・屋久島の宮之浦港沖北約11キロの海上で、インドネシア人12人が乗り組んだ元旅客船「マサゲナ」(833トン)から第10管区海上保安本部(鹿児島市)に「機関室に浸水し、電源喪失した」と救助を要請する無線連絡が入った。10管は自力航行ができない状態とみて、巡視船と飛行機を現場に向かわせた。

四国フェリー(高松市)によると、マサゲナは同社が所有し、岡山と小豆島を結ぶフェリー「第五しょうどしま丸」(定員480人)として使われていた。20日に売却され、25日に尾道(広島県)を出港し、インドネシアに向かう途中だったという。

26日午前9時45分ごろ、鹿児島県屋久島の宮之浦港の北11キロの沖合にいるインドネシア船籍の元旅客船マサゲナ(833トン、12人乗り組み)から、機関室が浸水して自力で航行できなくなった、と第10管区海上保安本部(鹿児島市)に無線で救助要請があった。

10管によると、12人は無事。午後5時50分までに全員をヘリでつり上げて救助し、屋久島に運んだ。船は島に沿う形で南東方向に流されたため、10管の巡視船が、岸に近づかないよう沖合にひく作業をした。

マサゲナは岡山と小豆島を結ぶフェリーとして使われていた旅客船で、売却されて広島県尾道市からインドネシアに向かっていた。

もし、保安庁又はPSC(外国船舶監督官)が出港前に厳しく検査していれば、被害を最小限に 出来たかもしれない。

尾道港に接岸しているマリア(売船前の姿)

波が高い海域を運航できるように建造されていなかった。十分な装備で出港したのか??

25日午後9時45分ごろ、西表島の西約40キロ沖合で、カンボジア国籍の売船「NITTSU NO3」(約200トン、乗組員8人)が浸水し、26日午前3時22分ごろ、西表島西北西約24キロ(水深約1200メートル)沖合で沈没した。

救助要請を受けた石垣海上保安部の巡視船と石垣航空基地のヘリが出動し、乗組員全員を救助した。けが人はなかった。

同保安部によると、沈没した船はフィリピン向け売船のため、回航中だったが、荒天避難のため石垣港へ向かっていたが、高波などで、船体後部の船室まで浸水し、その後も浸水が止まらず、船体が傾斜、沈没の可能性が高くなったため、救助を要請した。

また、沈没船にあったドラム缶などが漂流しているため、同保安部では付近を航行する船に注意を呼びかけている。

26日未明西表島の近海でフィリピン人の乗組員8人を乗せた船が高波にのまれて沈没しました。乗組員は全員無事救助されました。沈没したのは広島の尾道からフィリピンに向かっていたカンボジア国籍の船NITTSUナンバー3で、25日午後10時前、『高波に飲まれ船が浸水している』と海上保安庁に救助要請が入りました。

第11管区石垣海上保安部は巡視船2隻とヘリコプターを現場に派遣し、26日午前3時過ぎ、フィリピン国籍の乗組員8人を無事、救助しました。乗組員は疲労が激しいものの怪我などはありませんでした。船は乗組員が救助されたおよそ7分後に急激に傾き、まもなく沈没しました。

平成19年8月26日 浸水沈没する N号

25日午後9時45分頃、台湾RCC(救助調整本部)から当本部に西表島西約40キロメ-トル沖合いで、「売船のためフィリピン向け回航中のN号(199トン カンボジア国籍 8名乗組(全員フィリピン人)が海上荒天のため浸水中。」との救助要請を受け、午後10時45分、当本部は石垣航空基地MH713(潜水士2名同乗)と石垣保安部の巡視船「ばんな」を現場に急行させました。

潜水士2名を降下させ該船の浸水箇所の調査等を実施中のところ、26日午前2時10分頃から浸水が増し、船体が傾斜、沈没の可能性が高くなったので伴走警戒中の巡視船ばんなにより該船に強行接舷し午前3時13分、該船乗組員8名及び潜水士2名の計10名を無事移乗させ救助しました。

その後、該船は急激に傾斜、転覆し午前3時22分に西表島北西約24キロの海上において沈没しました。

浸水・転覆等の原因については石垣保安部にて調査中です。

サブ・スタンダード船のメリットそして取締る側の官庁の現実を考えるとサブ・スタンダード船 はなくならない。 第2回パリMOU・東京MOU合同閣僚級会議の結果について (サブスタンダード船の排除に向けた我が国の決意を表明)(国土交通省のHP) はリップサービスなのである。

船籍国と船級協会 合田 浩之 (一般財団法人 山縣記念財団)

Citing the fact that Cambodian-flagged ship could ruin Cambodia's reputation, Mr. Hun Sen wants reform for the flag-of-convenience registry. One thing which already tarnished Cambodia's image was the fact that Mr. Hun Sen miserably failed to see his thuggish response to the criticisms leveled by Prof. Yash Ghai, the UN Special Envoy for Human Rights, on his government. To find out who is ruining Cambodia's reputation, Mr. Hun Sen needs not look father than his own mirror. (Photo Reuters)

Tuesday, April 4, 2006

PM: Flag-of-Convenience Registry Needs Reform

By Kay Kimsong

THE CAMBODIA DAILY

Prime Minister Hun Sen has called for Cambodia's flag-of-convenience shipping registry to be reformed, citing the damage that could be caused to the nation's reputation if terrorists used Cambodia-registered vessels.

On Monday, however, the Council of Ministers official in charge of the ship registry concession deal with a South Korean company said the system was going well and should be continued.

"The flag registration system has to be reconsidered, otherwise the reputation of Cambodia will be destroyed by a foreign ship," Hun Sen said on Friday at the annual meeting of the Ministry of Public Works and Transportation. "If there was a terrorist problem on a Cambodian ship, how spoiled would the name of Cambodia be?"

He said that in the past, a ship flying the Cambodian flag had been caught smuggling drugs to France, and that another was found transporting missiles.

Council of Ministers Secretary of State Seng Lim Neou said the flag-of-convenience system should continue with the South Korean company Cosmos Group. "We can't stop a business contract midway," he said. "If we do so, the company can sue for breach of contract."

A 10-year contract with Cosmos was signed in 2003, when the Council of Ministers took over the supervision of the registry from the Transport Ministry, he said.

He added that the government has earned $1.5 million in three years from the fees for registering foreign ships. He said that the only problem in recent years has been a Cambodian vessel caught illegally fishing off Australia in September, manned by a crew of Chilean, Peruvian, Spanish, Ukrainian and Russian sailors.

"Now everything is smooth, in good condition and strictly controlled," he said.

The government discontinued its registry concession with the Cambodian Shipping Corp after a Cambodian-registered freighter, The Winner, was seized by the French Navy in June 2002 and found to be smuggling cocaine.

The Russian coast guard fired warning shots Saturday to stop a Cambodian-flagged vessel that was fishing illegally off the coast of the Bolshoi Pelis island; the vessel maneuvered dangerously at high speed in an attempt to escape, the Interfax news agency reported on Monday. A second Cambodian-flagged vessel was also discovered fishing illegally on Monday in the same area, Interfax reported. Both vessels, the Daring and the Aquarius 1, were being escorted to Russian polls.

At the end of March 2004, more than four years after the disaster, the French judge Dominique de Talancé has closed the "ERIKA" file accusing 19 different entities! It's a record: she combed very wide and the list is long, starting with the Ship's Captain to the Coastal state, including the ship owner, classification society etc.

In this she is completely right as the case of the "ERIKA" and that of the "PRESTIGE" shows that the whole maritime transport chain is implicated in these two catastrophes. Of course with different degrees of responsibility, however all 19 accused entities have for the moment been cited as having comparatively the same level of culpability: it will be for the courts to define who is at fault and who is to be exonerated.

In this there is a great improvement with respect to past practices. Some will remember the dramatic disaster in March 1980 of the old Malagasy tanker "Tanio" loaded with 20,000 tons of the same Heavy Fuel n°2, who broke in two and sunk in stormy weather off the French coast in the English Channel . It was a very similar case, except that eight sailors lost their lives in that catastrophe. That affair was not judged in the same manner, was it because there were a lot of French interests at stake?

But coming back to the "ERIKA", without wanting to pre-judge what the courts will decide. In all these maritime dramas the sailors as well as the coastal populations, the fauna and flora, pay heavily when the "misfortunes of the sea" degenerate into an ecological catastrophe.

In these cases there exists a highly responsible entity who regularly escapes all forms of sanction and who should normally be in the front line to receive the heaviest penalties: that entity is the flag state.

It is that flag state that registers the vessel so it has to have resources and sufficient personnel with maritime expertise to impose and control the maritime legislation on its ship. It is this same flag state therefore that should see that the conventions, international rules and standards are respected onboard all vessels registered under its flag in accordance with requirements. It is that flag state that should ensure the seaworthiness of each of these vessels, fit for service for which she is intended, renewing the certificates as well as the navigation certificate and safe manning certificate during the regular inspections and surveys performed by qualified inspectors and competent surveyors with a good level of experience. That's the job of a responsible administration from the point of view of Safety and Protection of the Maritime Environment.

But alas this is not always the case for small countries that often have no maritime traditions and even less a strong and accountable maritime administration behind to support their fleet and preserve maritime safety and impose the relevant legislation! These micro-countries delegate their authority to a Recognized Organisation (R.O), generally a Classification Society, that can in certain cases be the same one that is in contact with the ship owner for the classification of his vessel. Too many unscrupulous ship owners, those who tarnish the image of Shipping, are looking for these flags without states (without a genuine link) to make their most profitable business in a tax fee Paradise, which will transform into Hell for the Sailors.

Following on this there is a classification evaluating the performance of the flag states according to their seriousness. They are classed according to numerous criteria taking into account their compliance with basic international conventions ( Marpol, Solas, STCW, Load Line, OIT, FIPOL), whether they are on the black or the white lists of the Paris or Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) and US Coast Guard , depending also of deficiencies and detention rates, and whether or not they have good relations with the International Maritime Organisation.

Not forgetting also their relations with the Classification Societies, are they members of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) ?

The number of old vessels flying their flags also plays a part for their respectability classification including annual loss statistics. We notice however that the greater number of registrations, not the lesser, pose serious problems, such as Panama and other banana republics, not forgetting Malta who joined the European Community on the 1st May and has still not ratified the Marpol convention! Astounding for the 5th fleet in the world!….

Hopefully a clause insists that it ratify the principal international conventions as quickly as possible.

Imagine a vessel identified in a doubtful register, in the framework of all the previously mentioned situations, who has a record a long way from being clean, having had an important number of major and minor deficiencies found during port state controls (PSC) leading to days of detention abroad during the last years. In fact a heavy past record which comes to light following a maritime disaster of great importance, shipwreck of the vessel , loss of human lives and large-scale coastal pollution! Is it not possible in this type of case that the Coastal State, victim of this oil spill, as well as the families of the missing sailors could lodge a complaint before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) ?

This court exists with its head office in Hamburg. It's an independent and competent judicial body to deal with disputes arising out of the interpretation an application of the United Nations Convention for the Law Of the Sea ( UNCLOS - Montego Bay 1982). It was established by a United Nations convention and is called "Settling of Disagreements". Inaugurated in 1996 it is composed of 21 members.

This court is for the Law of the Sea, the equivalent of the International Court of Justice of Den Hague (Netherlands).

Its competence extends to the protection of marine environment. A nation who does not respect its obligations could be brought before this court. All nations have rights to the Main Sea, referring to that famous Freedom of the Seas that has governed maritime shipping for a long time.

Notwithstanding a nation also has its own obligations, made clear since 1982 during the elaboration of the Montego Bay convention on the Law of the Sea. It is on this precise point that the intervention of the ITLOS can be effective in the fight against non respectable flags: harassing them constantly by lodging complaints before this international court at each breach of a vessel flying their flag.

Consulted about a possible complaint by the coastal state against the flag state, following an oil-spill caused by a substandard ship, the answer of a judge of this court was clear: "…It is a very significant and difficult question. The ITLOS could know of any dispute between the flag state and the coastal state on this subject for insufficient control by the flag state of the polluting ship. It never was it and ,moreover, I do not know a case in which one sought to blame the flag state. It is a pity, because all the question of the responsibility for the flag state remains to be defined in international law. It is the one question of will of the sovereign states. It would be enough that France , for example, lodges a complaint against the Bahamas in connection with the Prestige affair in front of the ITLOS or an arbitration court to finally pose the problem in front of an international court. I believe that it would be an interesting contribution to the evolution of the international law on the matter. But I note the reserve of the states to enter this way…"

There is a good chance that constantly being pointed at and wearied by multiple convictions the incriminated state would "cleanup" its fleet by upwardly reviewing the standards to which it must be subjected and equipping itself with a competent maritime administration better able to control its vessels. Only presentable flag registrations would survive this necessary cleanup.

There are still too many countries on the Black and Grey Lists of the Paris and Tokyo MoU. These countries should either cease to practice maritime transport because of the menace they represent for the sailors and the environment or they should make the necessary efforts to get on to the White List grouping the presentable registrations.

Why, at each blatant crime of voluntary illegal oil discharge off its coast, would not a country, as a sovereign coastal state , lodge a complaint before that jurisdiction against the incriminated vessel's flag state ? No doubt, that the complaint would be admissible and that the consequent conviction would carry a fine in keeping with the committed fault, would have effective repercussions in the hunt for the polluters. Above all if there is an obligation for the flag state to restore the environment following any pollution incident.

For the same reasons the flag state has to be responsible of the acts of the ship owner . Especially in the dramatic case of seafarers left behind by their ship owner who disappears when the ship is seized in port. The flag state has many duties, it is normally the one and only link to which should be able to be attached with hope the seamen for payment of their unpaid wages and the expenses of repatriation towards their respective countries. Alas the truth is very different, disturbing, the flag state is always without any reaction in this particular cases and doesn't seem concern at all by this humanitarian problem.

Recently in Argentina, the International Transport Workers'

Federation (ITF) has carried out a study about this problem: it showed that during last 10 years, 8 ships were seized and derelict by their ship owners in Argentine ports, 6 of these "ships of shame"(S.O.S) were flying the Panama flag ! These bad behaviours deserved an action of the port state (Argentine) against the flag state (Panama) before the international court of Hamburg.

These new actions will give work to the ITLOS whom, it must be said, is all but dormant, treating only fishing disputes between states.

There is not any alternative that to bring such cases of maritime offences before the ITLOS because a sovereign state is not allowed to bring charges before its own jurisdiction against another sovereign state for acts holding with the exercise of its sovereignty.

The French magistrate , Dominique de Talancé, in charge of the Erika affair, is well placed to know this principle of jurisdiction immunity based on an "international courtesy" having to chair the relations of good vicinity between sovereign states!

Bad news on the 16th of June 2004, she failed in her attempt to lodge a complaint before the French jurisdiction against Maltese Maritime Authority for negligence in its inspections of the tanker Erika endangering seaman's life and complicity of pollution. Unfortunately, well defended by French clever lawyers, the MMA found the flaw in the first judgement before the Appeal Court in Paris . They succeed to demonstrate that MMA is a public authority, emanation of the Republic of Malta !

Can one speak about courtesy in the sinking of the Erika ?.. We hope that Mrs de Talancé is tenacious and will try to pose the dispute against the flag state before an international jurisdiction, the right one this time, the ITLOS for example.

What will happen if the other entities do the same and succeed to slip through the net of the French justice? The odds are that Captain Mathur, the ship's master, will be very lonely in front of the French judge when the Erika case will stand trial next year. Once more the focus will be entirely on Master, diverting attention from responsibilities of classification society , ship owner, port authorities , charterer, etc…the ship's captain will be The tree which hides the forest !

So, the International Maritime Organisation has a major role to play in cleaning up the international shipping by eradicating from the surface of the oceans the old sub-standard vessels and the easy registration flags who are lax in the area of maritime security.

The IMO is firmly harnessed to this very difficult task to make shipping safer as well as to improve shipping routes, all in order to preserve life at sea to a maximum approaching the zero tolerance. "He that would sail without danger must never come on the Main Sea" said an old adage , it means that the zero tolerance is quite impossible but all measures that contribute to the goal of maritime safety improvement and pollution prevention are very welcome. To this objective the use of the International Tribunal for the Law Of the Sea is a link, a trump that must not be neglected.

At sea there is no room for complacency and substandard flag state, these flags without states , where you can register a ship in a few minutes! We can no longer continue to transport no matter what,.. no matter how. Safer Shipping, Cleaner Oceans …

Capt. M.Bougeard

Master Mariner

Member of AFCAN

Panama, a small nation of just three million, has the largest shipping fleet in the world, greater than those of the US and China combined. Aliyya Swaby investigates how this tiny Central American country came to rule the waves.

Thanks to its location and slender shape, Panama enjoys a position as the guardian of one of the world's most important marine trade routes, which connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

For a hundred years the Panama Canal has provided a short cut for ships wishing to avoid the more hazardous route via Cape Horn.

Dubbed one of the seven wonders of the modern world, the 77km (48-mile) canal is a feat of engineering that handles 14,000 ships every year along its intricate lock system.

Many of these vessels fly the Panamanian flag yet the country itself has a limited history of trade.

Panama only has one small shipping line as well as a number of companies providing supplementary maritime services around the ports and canal.

Cheaper foreign labour

Most merchant ships flying Panama's flag belong to foreign owners wishing to avoid the stricter marine regulations imposed by their own countries.

Panama operates what is known as an open registry. Its flag offers the advantages of easier registration (often online) and the ability to employ cheaper foreign labour. Furthermore the foreign owners pay no income taxes.

About 8,600 ships fly the Panamanian flag. By comparison, the US has around 3,400 registered vessels and China just over 3,700.

Under international law, every merchant ship must be registered with a country, known as its flag state.

That country has jurisdiction over the vessel and is responsible for inspecting that it is safe to sail and to check on the crew's working conditions.